Tag: WWII

Native American Code Talkers

Today (March 27) marks the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II. The 69th Montana Legislature is honoring that date with Senate Joint Resolution No. 20. SJ No. 20 which recognizes the end of World War II and Montana’s veterans who served during that war. Over 75,000 Montanans served with distinction. Montana’s 163rd Infantry Division, 41 st Sunset Infantry Division, also known as the Fighting Jungleers, included over 230 Native Americans, representing eight tribals nations located in Montana. Kept as a national secret for decades after the war, we are now learning of the significant contribution some of these veterans played as Code Talkers, who used their native languages for communications in support of military operations. Members of the Crow, Assiniboine, Sioux, and Fort Peck tribes conveyed information that stymied German and Japanese troops with efficient coded messages.

The following articles further decribe the members of this elite group and celebrate their venerable part in the Allies’ victory over German and Japan.

Honoring an ARSOF Legend

Robert T. Frederick, Commanding General, First Special Service Force (1907-1970)

The Battle of Biak: “A Terrifying Glimpse Into the Soul of Mankind”

In the Spring of 1944, the small island of Biak—a stepping stone to the Philippines—was taken by the Americans.

Members of the 163rd Regiment Buried at the State Veterans Cemetery

The 163rd Regiment was composed of Montana National Guard soldiers who served in both the European and Pacific Theaters.

Special thank you to Mike Connelly, a long-time volunteer at the Military Museum for compiling this data from many and various sources.

World War II in Montana

Battle of Monte Cassino – Allied Mistake, or Brutal Necessity?

The Battle of Monte Cassino began on January 17, 1944. The area was a stronghold for Germany, which held the Garigliano, Uri, and Rapido valleys, forming the Gustav Line. The rugged terrain created a natural fortress, giving the town the defensive high ground and creating a strategic nightmare for the Allies.

The Arsenal of Democracy’s Oversized Training Guns

Our friends at the Fort Harrison Military Museum in Helena, Montana, contacted us about an interesting discovery they made while searching through one of their storage sheds. Sorting through dust-covered artifacts, our friends at the museum stumbled across a small treasure-trove of unique pieces of American firearms history they put on display: a group of the double-sized training aids representing key U.S. small arms of World War II and the immediate post-war period.

The Little Known Battles of Attu And Kiska: Retaking The Only US Soil Lost During WWII

War History Online

In the cold, desolate Arctic near Alaska in 1942, Japanese troops quietly invaded and took over two of the Aleutian Islands, considered to be North American soil, with barely any resistance. First, on June 6, they took nine Americans prisoner at a naval weather station on the island of Kiska, and the very next day, on the island of Attu, they captured 45 native Aleuts and an American couple from Ohio.

These two islands are so remote and barren that Attu, according to archeologists, had only a maximum of 5000 inhabitants in the several hundred years preceding its discovery by more recent Russian fur traders. Even when they arrived, one stranded Russian waited seven years before any other ship arrived and he could leave.

By the time WWII came around, the islands were sparsely inhabited, but the growing fear of Japanese in the Pacific sadly prompted American territorial authorities to move the native Aleut inhabitants to internment camps in Alaska. Of the 880 moved, 75 died in the camps due to infectious disease during the two years of internment. Sadly, it wasn’t only the evacuees that suffered. The U.S. didn’t evacuate all of the civilians from the islands – the 43 Native Aleuts and the American couple were still on Attu. When the Japanese took the island of Kiska, they killed two men, captured seven, and one escaped – for a while. He hid in a cave, subsisted on earthworms, and lost 80 lbs. After fifty days of starvation in a frozen wasteland, Senior Petty Officer William C. House finally surrendered himself. His surviving Navy brothers had since been moved to Japan and he soon followed. They remained there for the duration of the war.

Why Did Japan Want the Aleutians?

The Aleutian Islands are very remote (1200 miles from Alaska), barren, volcanic islands that are plagued by harsh weather can change on a dime from cold, still, and dense with fog to blasting winds that can drive a person down at 100 mph. There are few if any trees and they are almost unlivable.

Japan’s interest in the Aleutians was strategic. A few years before, U.S. General Billy Mitchell had said, “I believe that in the future, whoever holds Alaska will hold the world. I think it is the most important strategic place in the world.”

The Aleutians aren’t exactly Alaska, but Imperial Japan’s General Higuchi Kiichiro had a similar notion. He believed that if he controlled the Aleutians, Kiska and Attu specifically, he would control Northern Pacific sea routes. He wanted to prevent offensive attacks on Japan, separate and create a boundary between Russia and the U.S. (just in case Russia decided to gang up with the Americans and together attack the Japanese), and to create air bases from which to make offensive attacks.

Japanese troops raise the Imperial battle flag on Kiska after landing on 6 June 1942. Japanese troops raise the Imperial battle flag on Kiska after landing on 6 June 1942.

Taking the Islands The Japanese, under the command of Colonel Yasuyo Yamasaki, arrived in Kiska on June 6, 1942.

They easily took the island, and the next day began invading Attu as well. The prisoners they took there were transported to a prison camp at Otaru, Hokkaido, where sixteen of them would die.

The soldiers, who would eventually number 2300-2500, were from Northern Japan and were accustomed to the cold and wind and had little difficulty working in Aleutian conditions.

From June to September the initial occupation numbering 500 or so Japanese soldiers was growing and preparations were being made. From September to October, the Japanese moved all operations to Kiska, leaving Attu undefended, but the Americans weren’t positioned to take the opportunity to act.

At the end of October, the Japanese returned to Attu under the command of Lt. Col. Hiroshi Yanekawa who established a base at Holtz Bay, where they remained undisturbed by Allied forces for 11 months.

Why Didn’t the U.S. Respond?

Part of the huge U.S. fleet at anchor, ready to move against Kiska. Part of the huge U.S. fleet at anchor, ready to move against Kiska. The Japanese attacks on Kiska and Attu occurred just six months after their attack on Pearl Harbor. U.S. forces were still reacting to the devastation and were trying to build up defenses in the Southern Pacific while simultaneously dealing with the European conflicts.

The U.S. did fly from other nearby Aleutian Islands to conduct minor bombing raids, but they didn’t have the ability to bring in ground troops until their victory in March of 1943 in the Battle of the Komandorski Islands in the Bering Sea.

That battle opened the sea lanes enough to finally respond to the Japanese invasion of Kiska and Attu.

Operation Landgrab

Battle of the Aleutian Islands Two months after Komandorski, the U.S. was ready to act. The Japanese had had limited supplies brought in – and only by submarine – once the sea lanes had been cut off. Still, the Japanese had knowledge of and acclimation to the island on their side. They may have been somewhat prepared, but they only numbered 2300 – certainly no advantage there.

Major General Albert Brown and 11,000 17th Infantry soldiers initiate Operation Landgrab on May 11, 1943. They landed at the north and south ends of Attu and had to make their way to Yamasaki’s position on the high ground that was further inland.

They faced little human opposition, but the island proved a formidable foe. This wasn’t a simple march to the inner parts of the island. The Americans were searching every nook and cranny for their enemy, and they were doing it in the snow, wind, and wet and they were not clothed for it. Neither did they have the equipment they needed for such a search. The powers that be thought this would be a simple in and out sort of mission and, thusly, didn’t take those precautions. They didn’t even bring enough food.

Many soldiers began to suffer from trench foot and gangrene and they were losing morale and physical strength due to extreme cold and hunger. When they did find Japanese soldiers, they were forced to fight the hardier men in intense small battles. The enemy soldiers lived by the Bushido Code, Way of the Warrior that forbid surrender and added to their fierceness in battle. They were warmer, better fed, and had more drive to fight.

Hauling_supplies_on_Attu American troops hauling supplies on Attu in May 1943 through Jarmin pass. Their vehicles could not move across the island’s rugged terrain. Still, it was the weather that was the biggest threat with driving winds, drenching rain showers, and freezing temperatures, causing more U.S. soldiers to suffer casualties from cold than from battle.

Somehow the bedraggled American troops were able to push the Japanese to Chichagof Harbor where they hid in caves or underground dugouts. The U.S. had the upper hand, and higher numbers and fortunes were looking poor for Yamasaki and his men.

The Japanese commander, to go forth in honor, decided to risk an attack on the U.S. His plan was to charge on the Americans, take their artillery, and then return to the cliff side hideaways and caves. They would then wait it out until the Imperial Army sent backup.

He launched his banzai charge in the early morning light of May 29th, to the shock of American troops – all the way through the posts to the rear of the American camp – hand to hand combat all the way. Once the Americans began using firepower, the Japanese had no chance, and those that had survived to make it nearly to the end began to commit suicide – many by grenade. A doctor from the field hospital had killed his patients, so they were gone too. He wrote in his diary, “The last assault is to be carried out.… I am only 33 years old and I am to die…. I took care of all patients with a grenade.”

A few very small groups of Japanese continued to fight until July, refusing to give up. Fewer than 30 survived to be taken prisoner. Around 1,000 of the 15,000 U.S. troops were killed.

Meanwhile, on Kiska, the Japanese holding that island heard of the mass suicide on Attu. When Americans arrived in August – better equipped with airplanes and Canadian bomber assistance – the bombs they dropped and in 95 ships they stormed Kiska with over 34,000 American and Canadian troops to take out the 5200 Japanese they expected to be there.

But the Japanese had left in July in a hurry with freshly brewed coffee still sitting in cups on the base.

Even though there was no enemy to fight, 200 Allied soldiers died in this non-battle. Some were victims of friendly fire, and others had unfortunate run-ins with booby traps and live ordnance.

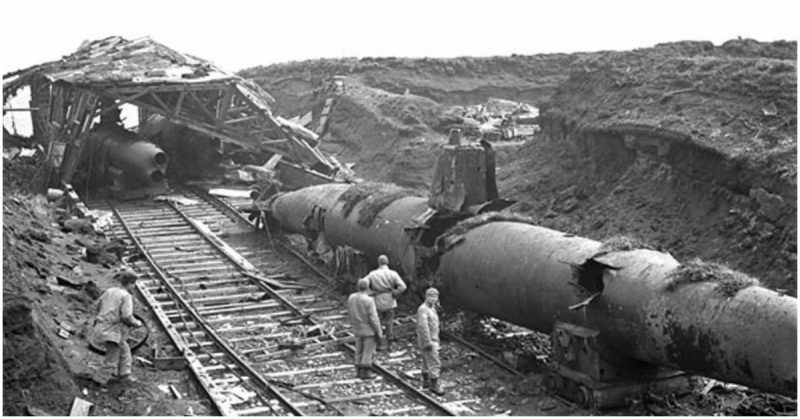

What’s Left

Troops march up the beach at Adak Island, during pre-invasion loading for the Kiska Operation, 13 August 1943. The LCM behind the soldiers is from USS Zeilin (APA-3). USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) is in the far right distance. Note the troops’ packs and M1 rifles. Troops march up the beach at Adak Island, during pre-invasion loading for the Kiska Operation, 13 August 1943. The LCM behind the soldiers is from USS Zeilin (APA-3). USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) is in the far right distance. Note the troops’ packs and M1 rifles. Seventy years later, both islands are like portals in time. Indentations from Allied tents can still be seen on the ground; cups of coffee are still there, and more than coke bottles litter the ground. The military occasionally makes an effort to remove live artillery and unexploded bombs from the island, but that task isn’t finished.

Archeologists and war historians are making an effort to study the sites because they are the only untouched battlefields that have been preserved completely. Because of the arctic conditions, decay is slow or non-existent, giving researchers a window into the past.

Former Vietnam War Army nurse from Helena receives Presidential Citizens Medal

“We’re glad she is a member of our post and we look forward to more connections with her,” he said. “It’s been a long time coming.”

Evans paved the way for the 1993 dedication of a sculpture in the nation’s capital honoring female veterans who served their country.

“I hope all Montana veterans are remembered and honored,” Evans said. “This medal is in honor of all the sister veterans.”