Category: World War II – European Theater

“Matters Canadian” and the Problem with Being Special

U.S.-Canadian 1st Special Service Force in World War II

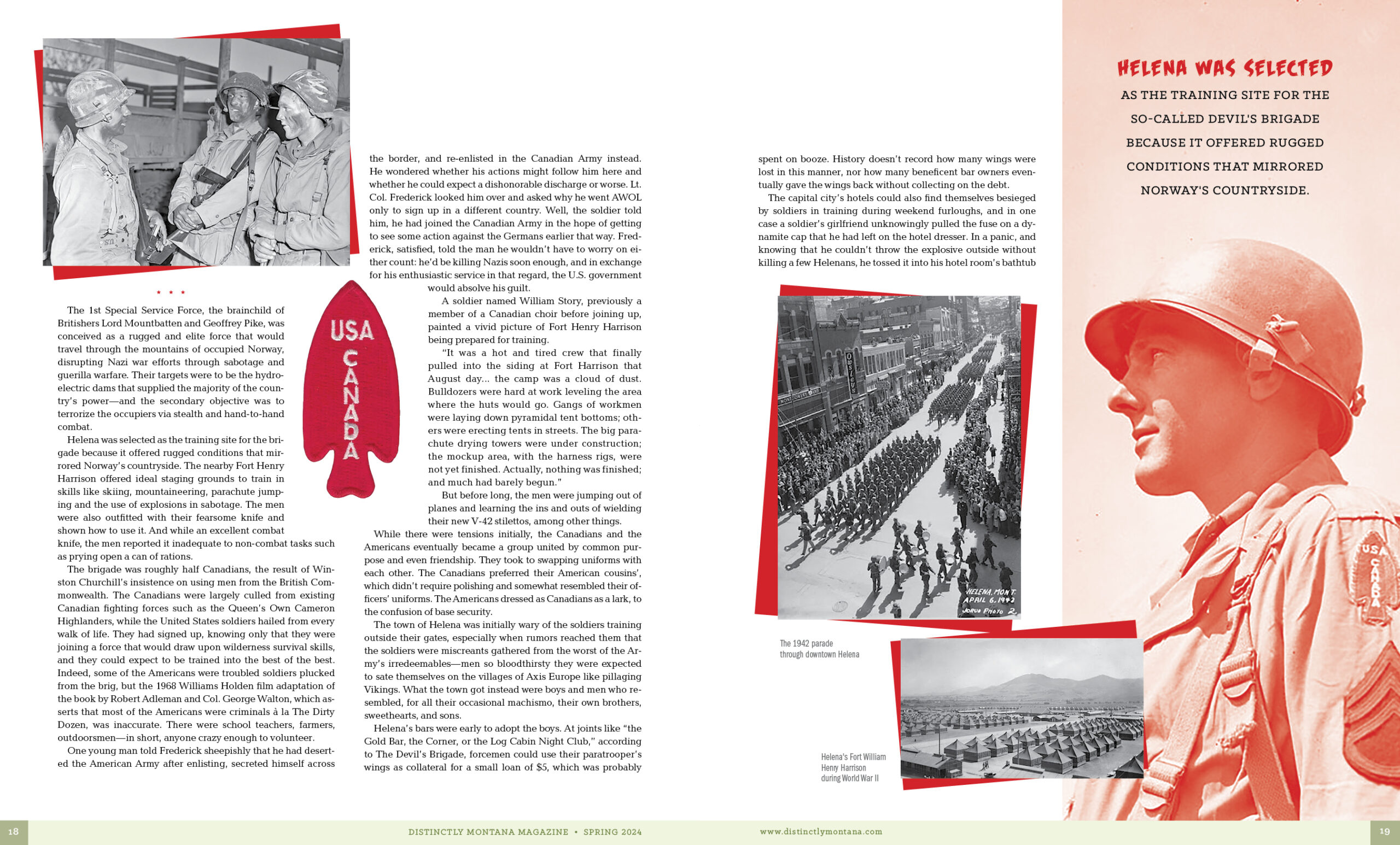

The Devil’s Brigade in Helena

This story first appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of Distinctly Montana Magazine.

Please click here for information on a subscription.

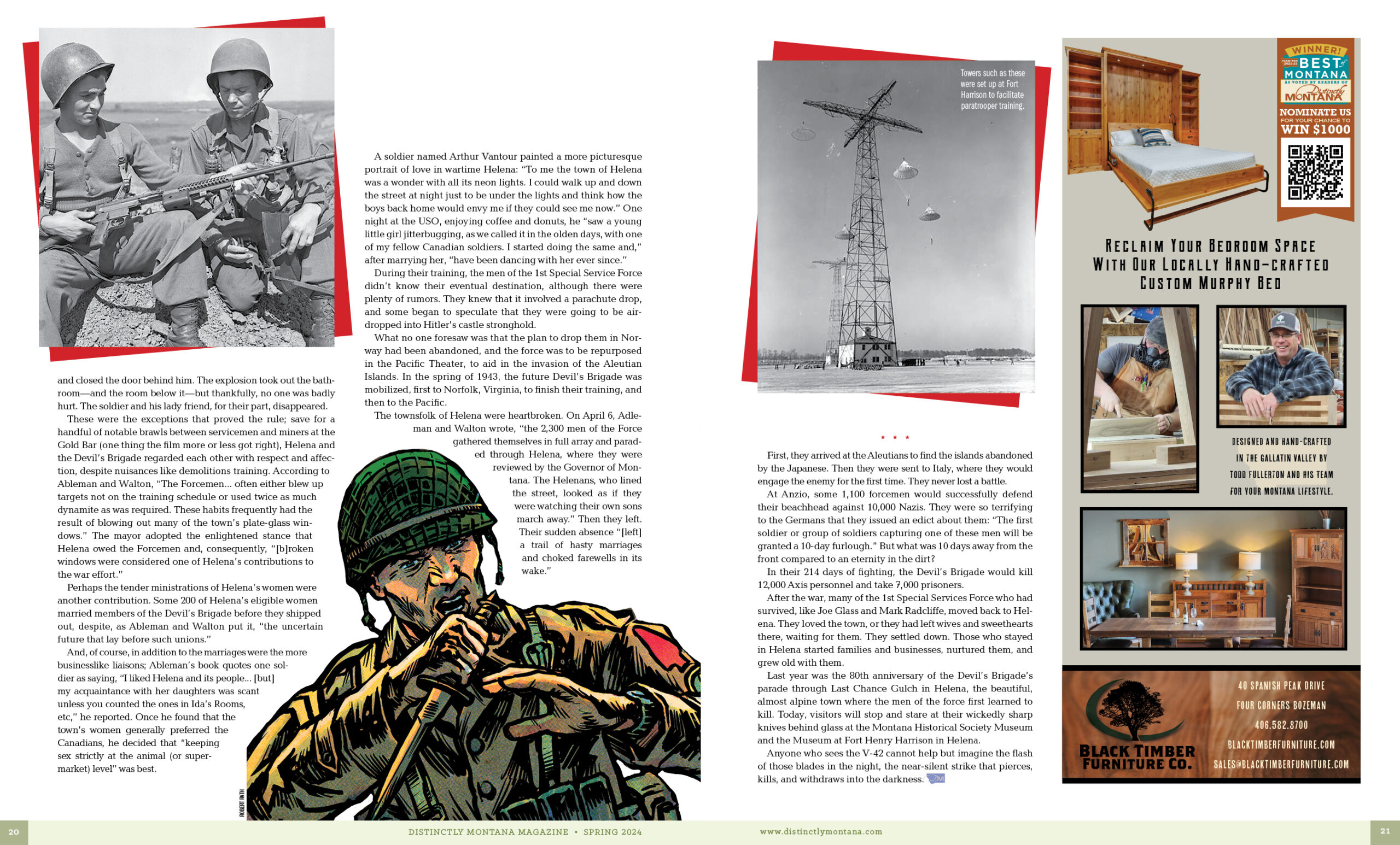

Fort William Henry Harrison and World War II’s Red Ball

Corporal Charles H. Johnson of the 783rd Military Police Battalion, waves on a “Red Ball Express” convoy near Alenon, France in September, 1944. The town was the approximate mid-point on the highway between the Normandy beaches and the ever moving American front lines. The site was used as a break point for changing and feeding drivers, refueling, and maintaining trucks. Courtesy National Archives.

Sources:

Carey, Christopher: The Red Ball Express: Past lessons for Future Wars, English Military Review, April, 2021.

Colley, David P.: The Road to Victory: The Untold Story of World War II’s Red Ball Express, (https://archive.org./details/isbn_9781574881738). Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-173, 2021.

Delmont, Matthew: The forgotten story of Black soldiers and the Red Ball Express during World War II, The Conversation Newsletter, April, 2021.

D’Este, Carlo, Decision in Normandy, Penguin Putnam, 1983, 1994

Eisenhower, Dwight D.: Crusade in Europe: A Personal Account of World War II, Vintage Books, December, 2021.

Hastings, Max: Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy, Simon & Schuster, 1984.

National World War II Museum, “Keep ‘em Rolling”: 82 Days on the Red Ball Express”, February 1, 2021

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, “Red Ball Express,” downloaded November 11, 2023.

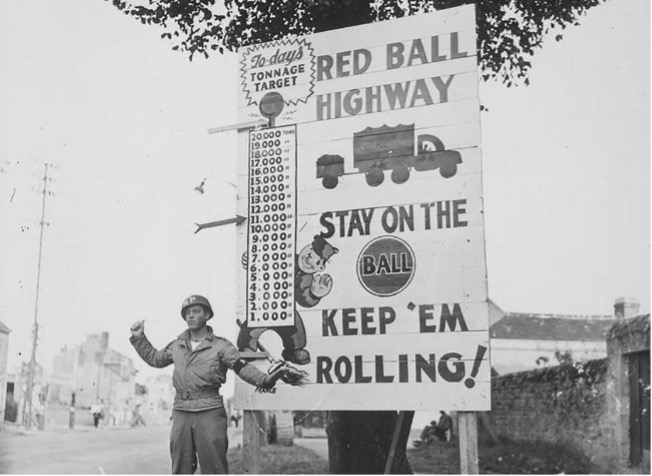

First Special Service Force’s General, Robert Tryon Frederick

Independent Record article by Philip Drake

Efforts are underway to raise money for a statue dedicated to the leader of the famed 1st Special Service Force that trained at Fort William Henry Harrison during World War II and was later named “the Black Devils” by German forces.

A GoFundMe site has been set up for Gen. Robert Tryon Frederick, to be erected in France, according to the page organized by Frederick’s grandson, Brad Hicks. He said his grandfather leading another command later liberated France from German troops in World War II and is still held in high regard there.

“He was legendary for leading his men into battle. Winston Churchill called him ‘The Greatest Fighting General of All Time.’ I just called him grandpa,” Hicks posted on the page.

The site has raised $1,365 toward its $15,000 goal, with Hicks noting the French have already raised $50,000.

“Communities across southern France now want to honor this remarkable American who gave them their freedom,” the page states.. “This is your chance to help make sure North America’s contributions to freedom in Europe are never forgotten.”

Frederick received eight Purple Hearts in WWII — more than anyone in the war; all of them as a colonel and general. He was charged with a new U.S.-Canadian commando force, that activated in July 1942 and was stationed at Fort Harrison.

The 1st Special Service Force saw most of its action in Italy where they were instrumental in breaking the German Winter Line. It played a key role at Anzio where they held a division-sized sector along the Mussolini Canal. Their final campaign was the liberation of Southern France. They were dubbed “The Black Devils” by the Germans and are also known as “The Devil’s Brigade.”

Frederick left the 1st Special Service Force during the summer of 1944, and was given command of the 1st Allied Airborne Task Force. In August 1944, Frederick, who at 37, was the youngest two-star general, led the airborne invasion of Southern France. They parachuted at night behind German lines and liberated the French Riviera.

“The people there still celebrate Aug. 15 as their Liberation Day, and they still consider Gen. Frederick their liberator,” Hicks said.

The 1st Allied Airborne Task Force then moved up the French Riviera coastline, taking Cannes unopposed on Aug. 24, 1944, and linking up with Frederick’s old unit, the 1st Special Service Force.

The Gen. Robert T. Frederick statue will be a bronze life-size sculpture, placed in a public park near his first command post in La Motte, France. The unveiling is planned for Aug. 15 — the 80th anniversary of the airborne invasion.

The chapter of non-profit Rotary International in La Motte, France is overseeing this community project and fundraising campaign.

Bill Woon, a Helena resident and member of the 1st Special Service Force Association who has written about the Black Devils, said any recognition of Frederick is a worthy project.

“He was the perfect leader for the 1st Special Service Force,” he said. “He knew how to command his men and lead his men and they would go to hell and back for him — and they did.”

Hicks, who was 7 when his grandfather died in 1970, is optimistic the money will be raised.

“I think the real story is that 80 years after the fact, the people of Southern France look up to him as a hero,” he said. “Aug. 15 is their Liberation Day. Even bigger, they have not forgotten the Canadians and Americans who liberated them. The statue of my grandpa is for all of them.”

The GoFundMe site is at https://bit.ly/3QlUOah.

‘It was just amazing’: 80 years ago 1st Special Service Force paraded down Last Chance Gulch

BILL WOON

First Special Service Force Association

Apr 6, 2023

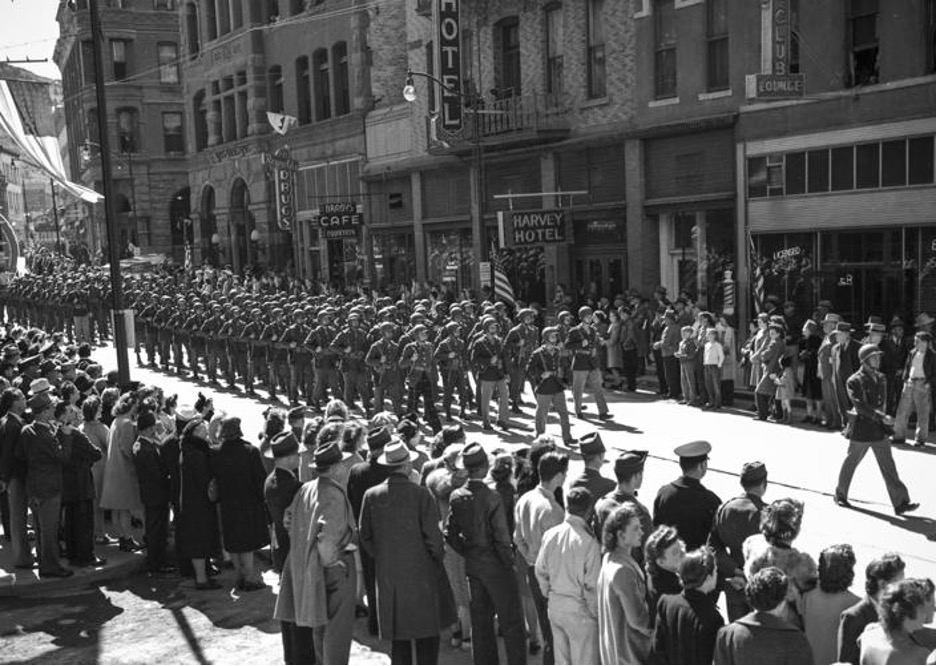

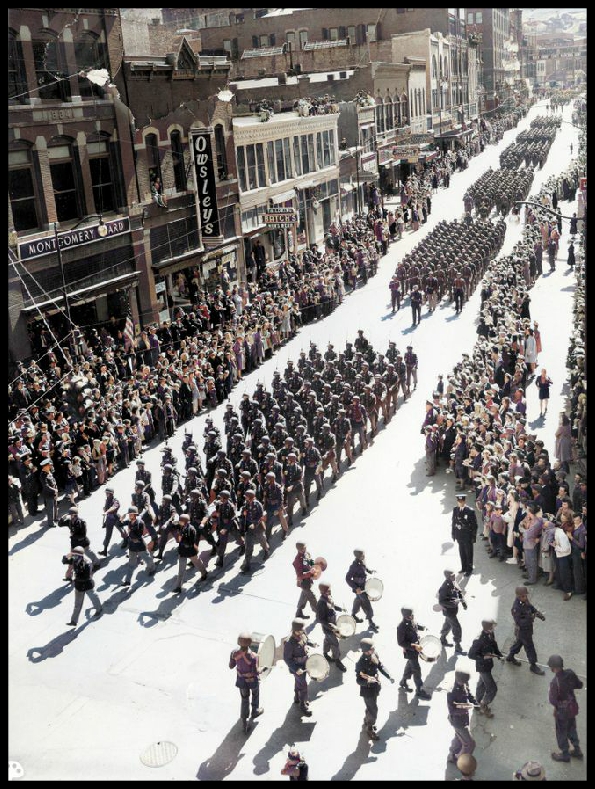

It was 80 years ago Thursday the 1st Special Service Force paraded down Last Chance Gulch as a farewell to Helena as they left for the East Coast for more training and eventual deployment to the Pacific and then Mediterranean Theaters of World War II.

The force was a unique joint Canadian-American top-secret unit under Lt. Col. Robert T. Frederick on July 9, 1942, at Fort William Henry Harrison west of Helena and later became known as the “Black Devils” by the Germans.

It was airborne-trained and highly skilled in mountain operations and amphibious assaults with tough, physical training concentrated on weapons proficiency and demolitions. When tested by the U.S. Army prior to deployment, the FSSF scored the highest in infantry proficiency of any unit in the Army.

The 1st Special Service Force saw most of its action in Italy where they were instrumental in breaking the German Winter Line, which was a series of mountains and ridges heavily defended by the German Army and had stymied the Allied advance to liberate Rome.

The Force then played a key role at Anzio where they held a division-sized sector along the Mussolini Canal. Aggressive patrolling and raids by the blackened faced Forceman earned them the nickname “Black Devils” by the Germans.

Members of the 1st Special Service Force were the first Allied troops to enter Rome on June 4, 1944.

Their final campaign was the liberation of Southern France. The Force seized two islands off the coast of Southern France to open the way for the Allied landing force, and then fought northeast along the coast through the towns of Grasse, Plascassiere and Menton where the unit was deactivated on Dec. 5, 1944.

In 251 days of combat the Force suffered 2,314 casualties – 134% of its combat strength. They captured 30,000 German prisoners, won five U.S. campaign stars and eight Canadian battle honors.

They never failed a mission.

Jim Cottrill of Helena was 4 years old at the time and remembers that parade of April 6, 1943, well.

“There were a helluva lot of people and I think the whole town turned out,” he said. Cottrill was with his mother and he said they walked down the hill to the parade and stood at Sixth Avenue and Last Chance Gulch, where a Montgomery Ward store used to be.

“They were impressive,” he said of the soldiers. “They came down that street and they marched. You could tell they were well-trained and ready to go.”

He said they were loved by the community as a lot of Helena residents had them over for Sunday dinners and holidays. Cottrill said many of the soldiers came back to Helena after the war and returned to their sweethearts and wives.

He said those who returned never talked much about their adventures.

Cottrill said one was Roy Hudson, who started a furniture store. He had been shot in the leg trying to rescue a buddy.

“I asked him if he was scared, he said, ‘Nah, those Germans couldn’t shoot worth sh*t,’” Cottrill said.

The surviving veterans of the FSSF dedicated a monument to their fallen brothers in August 1947 in Helena’s Memorial Park. The Cenotaph east of the monument includes the names of 488 men who made the ultimate sacrifice in World War II.

Most gratifying to the veterans of the FSSF is that its traditions and honors have not died but are carried forward, with its lineage embracing the outstanding active Special Forces units of two great democracies: The Canadian Special Operations Regiment and the United States Army Rangers and Special Forces.

On Feb. 3, 2015, Congress presented the Congressional Gold Medal to the 1st Special Service Force, “In recognition of its superior service during World War II.”

There were 43 original FSSF veterans attending the ceremony at the U.S. Capitol, along with over 800 family members, friends and members of Congress.

On Aug. 21, 2015, those veterans presented their Congressional Gold Medal to Fort William Henry Harrison, where the force trained 73 years earlier.

Cottrill does not know if Helena has ever had a bigger day than that parade 80 years ago.

“It was just amazing, the people all turned out,” he said. “They clapped and yelled.”

“The people of Helena really went all out for them,” Cottrill said. “They were proud to be what they were and the people just loved them.”

Independent Record Staff Writer Phil Drake contributed to this story. Bill Woon is with the First Special Service Force Association. Raymond Read is with the Montana Military Museum. For more information, contact Woon at 406-461-7485, or Ray Read of the Montana Military Museum, where there is a large collection dedicated to the Black Devils, 406-235-0290.

Montana’s Participation in World War II

Information highlighting some but not all, of Montana’s participation in the Second World War, or as it is known, World War II. It is provided it to you as a testament to Montana’s World War II generation, their dedication to duty and sacrifice to keep our nation free from tyranny.’ While May 8th was being celebrated as V-E day in Europe, many Montanans were fighting in the Battle of Okinawa. The Battle of Okinawa (April 1, 1945-June 22, 1945) was the last major battle of World War II, and one of the bloodiest. On April 1, 1945—Easter Sunday—the Navy’s Fifth Fleet and more than 180,000 U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps troops descended on the Pacific island of Okinawa for a final push towards Japan. The invasion was part of Operation Iceberg, a complex plan to invade and occupy the Ryukyu Islands, including Okinawa. Though it resulted in an Allied victory, kamikaze fighters, rainy weather and fierce fighting on land, sea and air, it led to a large death toll on both sides. Montana’s 163rd Infantry Regiment Montana’s 163rd Infantry Regiment, 41st Infantry Division, the Jungleers, was called to Active duty on September 16, 1940 for one year of training, and on the same day the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 introduced the first peacetime conscription (for men between 21 and 45) in United States history. • March 11, 1941: United States President Roosevelt established the Lend Lease Act allowing Britain, China, and other allied nations to purchase military equipment and to defer payment until after the war. • August 1941: President Roosevelt signed an extension of service of 6 months for those Americans who been called up in 1940, such as the 163rd Infantry training at Fort Lewis, Washington. • December 7, 1941: The United States came under attack by Japanese Forces at Pearl Harbor and locations throughout the Pacific. • December 8, 1940: The United States declared War on Japan. • December 11, 1940: Germany and Italy declare war on the United States. The United States reciprocates and declares war on Germany and Italy. The largest ever mobilization of American manpower continued, ultimately calling up over 15 million U.S. men and women to serve from 1941 to the end of hostilities in 1945. Over 75,000 Montanans were a part of that force. The 163rd Infantry Regiment served with distinction on the west coast of the United States until its departure to Australia in April 1942. This Regiment served as a part of the Southwest Pacific Command going on to fight in the Pacific Theater of World War II. The 163rd Infantry Regiment was recognized as the first U.S. unit to defeat Imperial Japanese Forces in the Battle of Sanananda, Papua, New Guinea in January 1943. It was subsequently recognized by the 28th Montana Legislative Assembly by resolution and in a famous painting by Irwin ‘Shorty’ Shope in April 1943. The 163rd Infantry Regiment served in the Pacific Theater in three major campaigns and a battle; the Papuan Campaign of 1943, winning the battles at Sananada, Gona, and Kumsi River; the New Guinea Campaign of 1944, winning the battles of Aitape, Wadke and ‘Bloody” Biak; the Southern Philippines Campaign of 1945, winning battles at Zamoanga, Sanga Sanga Island; and the Battle of Jolo and the key village of Calinan against seasoned Japanese land forces. This battle was stopped only because of the cessation of hostilities due to the dropping of the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Regiment finally became an occupation force on the Japanese mainland. The 163rd was demobilized in Japan, January 1, 1946, and sent home by ships. First Special Service Force The First Special Service Force was a joint US-Canadian special operations force secretly formed at Fort William Henry Harrison near Helena, Montana in July 1942, to organize and train for Operation Plough. Operation Plough included plans to attach a hydro-electric target in German-held northern Norway responsible for creating heavy water for Germany’s atomic bomb. The unit went on to serve in both the Pacific theater and European theaters, with battle credits in the Aleutians, Naples –Foggia, Rome –Arno, Southern France, the Rhineland and Southern France. They were inactivated December 1944 without losing a battle and with battle casualties’ equivalent to 137 % of its strength. Camp Rimini War Dog Reception and Training Center Camp Rimini War Dog Reception and Training Center was established at Camp Rimini, west of Helena where it trained as a part of the effort to disrupt the Axis power. It went on to acquit itself along military air routes as search and rescue services. They provided specialized transport in remote areas of the Northern Hemisphere such as Newfoundland and in Europe during winter operations as providing transport of war materiel to our American forces. 7th Ferrying Command, Air Transport Command The Army Air Force organized and trained bomber forces throughout Montana at such locations as Great Falls, Lewistown, and Cutbank. The 7th Ferrying Command, Air Transport Command was formed at Great Falls (Gore Hill) and at East Base (now Malmstrom AFB), Montana to carry out the mission of providing aircraft and critical supplies to our allies over the Great Circle Route, a critical part of Global War Air Operations. Fort Missoula Fort Missoula became an alien detention camp housing Italian sailors who had been caught up in the war from 1942 to 1943. After working with local farmers and ranchers, many of the men went on to immigrate to the United States. Triple Nickels Specialized units such as the African-American, segregated, 555th Parachute Battalion, known as the Triple Nickels, trained and fought forest fires throughout Montana and the Northwest. The Home Front The people of Montana supported the war effort in many ways on the Home Front, providing food, and other strategic supplies and minerals, meeting or exceeding the quotas for the eight War Bond Drives. Montanans support, fought, were wounded and died in all theaters of World War II. As Joseph Howard Kinsey wrote in his book “High, Wide, and Handsome” of the more than 15 million men and women in the U.S. armed forces during “World War II, Montana furnished 75,000” to the effort. “Proportionately this was near the top of all states. In World War II, as in World War I, Montanans were quick to enlist and they were healthy; the proportion rejected because of physical defect was smaller than the national average. Montana’s death rate in World War II was only exceeded by that of New Mexico in proportion to population.”

Victory in Europe (V-E Day)

“Our Victory is only Half Over”

Victory in Europe, or V-E Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allied Nations of Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender of its armed forces. German military leaders signed the surrender documents at various locations in Europe on May 7, 1945. The surrender prompted mass celebrations in European and American Cities. President Harry S. Truman dedicated V-E Day to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had died just weeks earlier, and is quoted with saying “Our victory is only half over” in reference to continued fighting in the Pacific Area. On May 7, 1945, both Great Britain and the United States celebrated Victory in Europe Day. Cities in both nations, as well as formerly occupied cities in Western Europe, put out flags and banners, rejoicing in the defeat of the Nazi war machine. The largest ever mobilization of American manpower, ultimately calling up over 15 million U.S. men and women to serve from 1941 to the end of hostilities in 1945, over 57,000 men and women seeing combat but a total 75,000 Montanans served World Wide. Proportionately this was near the top of all states. Montanans were quick to enlist and they were healthy! The proportion that was rejected because of physical defect was smaller than the national average. Montana’s death rate in World War II was exceeded only by that of New Mexico, in proportion to population. Montana had the record of oversubscribing first in eight World War II savings bond drives. The eighth of May spelled the day when German troops throughout Europe finally laid down their arms: in Prague, Germans surrendered to their Soviet antagonists, after the latter had lost more than 8,000 soldiers, and the Germans considerably more; in Copenhagen and Oslo; at Karlshorst, near Berlin; in northern Latvia; on the Channel Island of Sark—the German surrender was realized in a final cease-fire. More surrender documents were signed in Berlin and in eastern Germany. The main concern of many German soldiers was to elude the grasp of Soviet forces, to keep from being taken prisoner. About 1 million Germans attempted a mass exodus to the West when the fighting in Czechoslovakia ended, but were stopped by the Russians and taken captive. The Russians took approximately 2 million prisoners in the period just before and after the German surrender. Meanwhile, more than 13,000 British POWs were released and sent back to Great Britain. Pockets of German-Soviet confrontation would continue into the next day. On May 9, the Soviets would lose 600 more soldiers in Silesia before the Germans finally surrendered. Consequently, V-E Day was not celebrated until the ninth in Moscow, with a radio broadcast salute from Stalin himself: “The age-long struggle of the Slav nations… has ended in victory. Your courage has defeated the Nazis. The war is over.”

Camp Rimini War Dog Reception and Training Center

Camp Rimini War Dog Reception and Training Center was established west of Helena. Dogs and soldiers were trained at the camp as a part of the effort to disrupt the Axis power. Going on to acquit itself in places along military air routes as search and rescue, it provided specialized transport in remote areas of the Northern Hemisphere such as Newfoundland. In Europe during winter operations the team provided transport of war material to our American forces. The Army Air Force organized and trained bomber forces throughout Montana at such locations as Great Falls, Lewistown, and Cutbank. The 7th Ferrying Command, Air Transport Command was formed at Great Falls (Gore Hill) and at East Base (now Malmstrom AFB), Montana to carry out the mission of providing aircraft and critical supplies to our allies over the Great Circle Route, a critical part of Global War Air Operations. Fort Missoula became an alien detention camp housing Italian sailors who had been caught up in the War 1942-43 with the result being a well disciplined and trustworthy population some of who went on to emigrate to the United States. Specialized units such the African-American, segregated, 555th Parachute Battalion, known as the Triple Nickels, trained and fought forest fires throughout Montana and the Northwest. The people of Montana supported the war effort in many ways on the Home Front, providing food, and other strategic supplies and minerals, meeting or exceeding the quotas for the eight War Bond Drives. Montanans support, fought, died and or wounded in all theaters of World War II, as Joseph Howard Kinsey wrote, In his book “High, Wide, and Handsome” of the more than 15 million men and women served in the U.S. Armed forces during the War period, Kinsey wrote, “– in World War II, Montana furnished 75,000 men and women to the effort. “Proportionately this was near the top of all states. In World War II, as in World War I, Montanans were quick to enlist and they were healthy; the proportion rejected because of physical defect was smaller than the national average. Montana’s death rate in World War II was only exceeded by that of New Mexico in proportion to population. Montana had the record of oversubscribing first in eight World War II saving bond drives.” Today less than 2,000 World War II count Montana as their home.