Despite watching from the sidelines for more than two years, America was surprisingly unprepared for the war that came on December 7, 1941. That is however, with the notable exception of U.S. small arms. Compared to any other combatant nation, American infantry weapons represented an embarrassment of riches. Even some of our firearms kept in reserve were the envy of lesser military forces. Americans quickly came to expect nothing but the best from the Arsenal of Democracy.

Tag: WWII

Battle of Peleliu – Revisiting a Meat-Grinder of the Pacific War

September 15 marked the anniversary of the start to the Battle of Peleliu. Spearheaded by the 1st Marine Division, Operation Stalemate II was to take less than a week. Instead, entrenched Japanese defenders utilized the island’s rugged terrain and an intricate system of caves and bunkers to inflict severe casualties on the Americans.

Battle of Iwo Jima – Returning to the Black Sands

On 19 February 1945 — 79 years ago today — the US Marine Corps began the bloody work of taking Iwo Jima from the Imperial Japanese Army. Casualties were extremely heavy — nearly 7,000 Americans killed and close to triple that number wounded. In today’s article, Capt. Dale A. Dye, U.S.M.C. (ret.) describes his experiences in visiting that historic volcanic island.

USS Montana arrives at new Pacific Fleet homeport in Hawaii

The Virginia-class fast-attack submarine USS Montana (SSN 794) arrived at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam following a change of homeport from Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia, December 23, 2024.

INDEPENDENT RECORD

By Lt. j.g. Paul Fletcher, Commander, Submarine Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet Public Affairs

The USS Montana, a Virginia-class fast-attack submarine, arrived Dec. 23 at its new Pacific Fleet homeport, Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam in Hawaii.

The $2.6 billion USS Montana, also known as SSN 794, changed its homeport from Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia, the U.S. Navy said in a news release. It marks the ninth Virginia-class fast-attack submarine home-ported at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam. It will be assigned to Submarine Squadron 1 and is expected to serve the nation with a range of missions around the world for more than three decades, officials said.

“We’re all very excited to be here in Pearl Harbor and we appreciate the great welcome,” Cmdr. John Gilligan, commanding officer of USS Montana, said in the news release.

He credited the crew for “extraordinary work in Virginia to get to this significant milestone.”

Capt. Aaron Peterson, commander, Submarine Squadron 1, met the Montana pier-side upon arrival.

“On behalf of the Pacific Submarine Force Ohana, I enthusiastically welcome the officers and crew of the good ship Montana, with the warmth, culture, and spirit unique to the state of Hawaii,” he said.

Before finishing its homeport shift from the East Coast, Montana completed a post-shakedown availability at Newport News Shipbuilding and was redelivered to the Navy in November 2024.

“Through a great effort by the crew, working with our industry partners, we’ve completed our availability and rejoined the Fleet. We’re ready to execute any task we’re called upon to complete throughout the Indo-Pacific,” Gilligan said.

Commissioned on June 25, 2022, at Naval Station Norfolk, Montana is the second warship to be named after the state, following the armored cruiser USS Montana (ACR 13).

The submarine is more than 377 feet long and can displace nearly 7,800 tons. Montana has a crew of nearly 140 sailors — all of whom have been named by Gov. Greg Gianforte as “honorary Montanans,” — and can support various missions, including anti-submarine warfare, anti-surface ship warfare, strike warfare, and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.

The U.S. Pacific Fleet Submarine Force provides strategic deterrence, anti-submarine warfare, anti-surface warfare, precision land strike, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and early warning and special warfare capabilities around the globe.

Ron Davis, chair of the Montana-based USS Montana Committee, praised the reaching of the milestone.

“It signals that the submarine is that much closer to being tasked to accomplish any of a number of different missions as part of the Pacific Fleet,” he said, adding the committee and all Montanans will continue to proudly support the Montana as it settles in Hawaii “and through her service life.”

The nonprofit, nonpartisan committee is a group of volunteers from across the state who support the USS Montana. It was endorsed by the governor and Legislature in 2017.

The ship is decorated with a Montana theme with state rooms named after Montana cities. Passageways are named for Montana rivers. The crew mess area, called the Big Sky Saloon, includes a Glacier Park panorama.

The submarine also has a tribal victory/war song to be played aboard the submarine when the crew is called to battle stations. And in honor of the Treasure State’s past of vigilante justice in the 19th century, the crew has adopted the nickname “The Vigilantes of the Deep.”

For more information, go to: https://ussmontanacommittee.us/.

Battle of the Bulge: A Montana Perspective on the 80th Anniversary

Press Release: Battle of the Bulge December 1944 - January 1945

Join the Montana Military Museum on historic Fort William Henry Harrison Thursday, December 19, 2024 from 9 AM-4 PM for a tribute to the Montanans who participated and sacrificed in World War II largest’s allied military battle against the German forces in the European war theater, Christmas 1944 and start of the New Year 1945.

Over three hundred Montanans in various units participated in this battle under the most trying of environmental conditions. acquitting themselves most admirably. Come and hear some of their stories. Colonel John Driscoll has been. Asked to speak about his and his co-author Randall LeCocqe ‘s recent book entitled, The Battle of the Bulge: A Montana Perspective.

Battle of the Bulge Perspective based on various reviews—–

On December 16, 1944, the serene winter landscape of the Ardennes forest erupted into chaos as German forces launched a massive surprise assault on Allied troops. This confrontation, known as the Battle of the Bulge, became one of the most critical turning points of World War II. The German plan was audacious: to divide Allied forces, encircle and annihilate several armies, and compel the Western Allies into negotiating peace. While the offensive initially succeeded, it failed, signaling the beginning of Nazi Germany’s decline.

The operation, code-named Wacht am Rhein (Watch on the Rhine), was carefully orchestrated by Adolf Hitler and his generals. Hitler believed a bold counteroffensive could reverse Germany’s losses following the Allied invasion of Normandy and their relentless push through France. The Ardennes forest, with its dense woods and rugged terrain, was chosen as the attack site because the Allies had lightly defended it, assuming it was an unlikely location for an offensive.

Germany prepared a massive force of 200,000 troops, over 1,000 tanks and assault vehicles, and extensive artillery. Three key armies spearheaded the operation: the Sixth SS Panzer Army led by

General Sepp Dietrich, the Fifth Panzer Army under General Hasso von Manteuffel, and the Seventh Army commanded by General Erich Brandenberger. Their mission was to break through Allied lines, capture Antwerp, and cripple the Allies’ supply chain.

At dawn on December 16, German forces struck with devastating artillery barrages, followed by infantry and tank assaults. Poor weather, including heavy fog, grounded Allied air support, giving the Germans a temporary advantage.

Entire divisions of unseasoned and fatigued American troops stationed in the Ardennes were caught off guard and overwhelmed. The German advance pushed Allied lines back, creating a 50-mile-wide bulge in the front—hence the battle’s name.

A pivotal moment unfolded in the Belgian town of Bastogne, a critical crossroads. German forces encircled the town, but the 101st Airborne Division, under General Anthony McAuliffe, held firm despite being heavily outnumbered. When the Germans demanded their surrender, McAuliffe famously replied, “Nuts!” The defenders of Bastogne endured relentless attacks and freezing winter conditions until General George S. Patton’s Third Army arrived to relieve them on December 26.

Although the Germans made significant early gains, their advance soon stalled due to logistical challenges. Fuel shortages left tanks stranded, and their supply lines stretched thin. Meanwhile, the Allies regrouped. By December 23, improving weather conditions allowed Allied air forces to strike back.

Bombers and fighter planes destroyed German supply routes and troop positions, turning the momentum in favor of the Allies.

By late December, the Allies launched a counteroffensive from both the north and south, closing in on the German bulge. The fighting was intense, with villages and towns changing hands multiple times. Exhausted and suffering heavy losses, German forces began retreating by early January 1945.

‘Bomb-blasted American foothold”: How a Butte man survived Wake Island, life as POW in WWII

By Tracy Thornton, Montana Standard

Shortly before 8 a.m. on a Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese began their assault on the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor. The two-hour surprise attack killed an estimated 2,403 American men and women, and nearly decimated the U.S. Naval fleet.

Five hours later, the Japanese would begin another bombing raid 2,300 miles away, at Wake Island and its smaller islands, Peale and Wilkes. Stationed on the islands were nearly 525 U.S. military personnel — the majority being Marines and sailors. More than double that amount was the number of American civilian workers also on the island, there to construct military facilities.

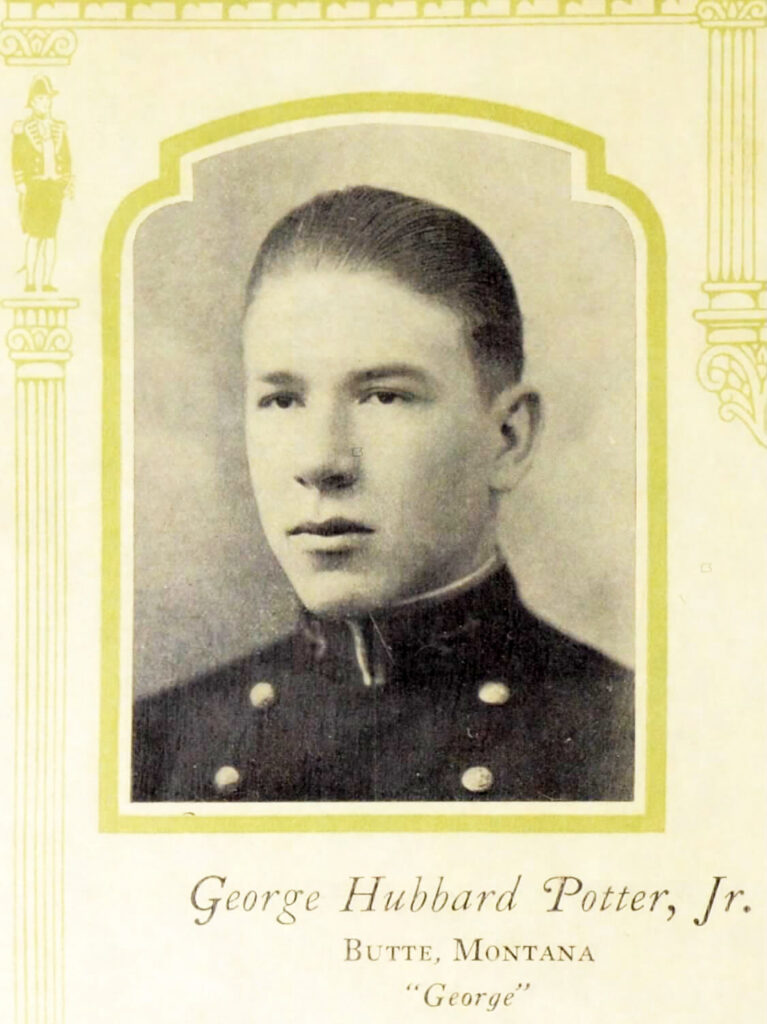

The troops on Wake Island fought the good fight; combatants included a Butte man, Major George Hubbard Potter Jr., who was second in command. In the end, though, the Americans were far outnumbered and surrendered two days before Christmas.

Major Potter, with the Marine Corps’ 1st Defense Battalion, previously was stationed at Pearl Harbor, where his wife Octavia and infant son George lived, but was shipped to Wake Island in October 1941.

Potter would spend the rest of the war as a prisoner of war. “Allied troops who had the misfortune to be taken prisoner by the Japanese during World War II quickly learned that the Geneva Convention might as well not exist. Indeed, they endured years of not only malnutrition and starvation, disease and general neglect — resisting all the while — but also torture, slave labor and other war crimes,” according to a 2016 article published by the U.S. Army.

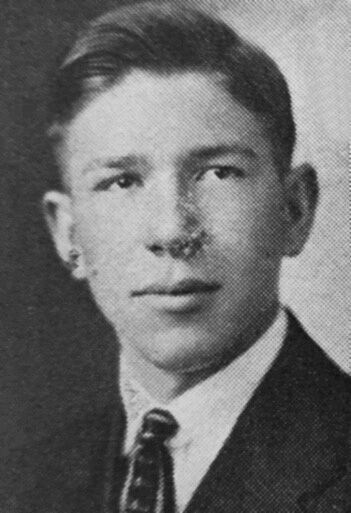

The son of George and Helen Potter, the younger Potter was born in 1906 in Ennis. His family, including two brothers, Ralph and Clyde, moved to Butte when he was young. A student at Webster Grade School, Potter graduated from Butte High School in 1923. Nicknamed “Gorg,” as a senior, he was president of the school’s mathematics club.

Potter would continue his education at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, graduating in 1927, and was then commissioned a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps.

Being a Marine was Potter’s chosen career. By 1936, he was a captain and later promoted to major.

After the Wake attack Potter was a POW for the next three years and eight months. He remained on Wake Island for Christmas 1941, but by Jan. 15, 1942, was a passenger aboard the Nitta Maru, a Japanese aircraft carrier, bound for Zentsuji, a prison camp in Japan. En route to the prison camp, five American sailors aboard that same ship were beheaded and then thrown overboard.

The only prisoners left on Wake Island were 98 American civilian workers, forced to work on various projects. According to the U.S. Naval Institute, all the men were executed by Japanese soldiers and buried in a mass grave on Oct. 7, 1943, “to eliminate the threat they might pose during the coming invasion” with American forces.

It wasn’t until April 1942 that Potter’s wife would receive any word from her husband. A message from Potter to his wife was broadcast via radio.

He said, in part, “Do not be worried about me. I’ll be all right but I am most concerned for your and the baby’s welfare, and about dad’s health.”

Potter would remain at Zentsuji until June 23, 1945, when he would be transferred to a camp located in the hills of Honshu, Japan.

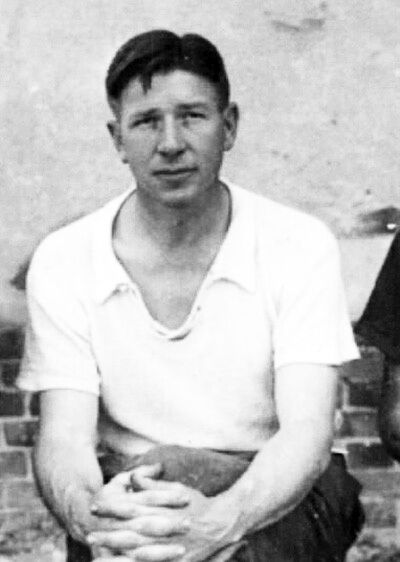

Now 50 pounds lighter, he would be liberated from this camp not long after Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, 1945.

In a post-war interview, Potter, who by then had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel, shared his war experiences with a Montana Standard reporter.

“The dwindled Yank force dug deeper and fought more fiercely for the bomb-blasted American foothold,” he said of the initial Battle of Wake Island.

Potter also talked about life in the POW camps, specifically Zentsuji.

“The Americans at the camp included 350 officers, enlisted men, nurses, and a few civilians,” he said.

Potter also stressed that the treatment of prisoners escalated as the war progressed. When it became clear that Allied forces would soon win the war, the atrocities got even worse.

“They became progressively that way as the tide of war set against them,” said Potter.

After serving 21 years, Potter, who would become a brigadier general, would retire from the Marine Corps in August 1948. The former Butte man died Sept. 17, 1983, in Florida, and is buried, along with his wife Octavia, at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

U.S. Special Forces in Vietnam

Merrill’s Marauders

Jedburghs OSS – WWII

Alamo Scouts (WWII)