African-American (Black) truck drivers of the Red Ball Express kept U.S. Army units supplied in the drive across France in the summer and fall of 1944 during World War II. Approximately two thousands of them received their training in driving and maintaining the 2½-ton trucks (deuce and a half) at Fort Harrison west of Helena, Montana.

After the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, American, British, and Canadian forces struggled to first secure and then break out from their newly acquired beachheads. By the middle of July, more than one million Allied soldiers were ashore in France, but they were confined to a front only 50 miles wide and 20 miles deep. By July 1, three weeks after D-Day, over 71,000 vehicles, most of them 2½-ton General Motors trucks as well as tanks, half-tracks, jeeps, and other combat vehicles had been unloaded at Omaha and Utah Beaches. Supplying the advancing Allied armies seemed an unsurmountable task. Under Hitler’s orders, the retreating German army had demolished all of the key deeper water port and dock facilities that otherwise could have been used for unloading critical supplies. In addition, Allied air forces had bombed most of the vital highway and railroad bridges in order to prevent counter attacking German forces from reaching the Normandy beaches. To complicate matters, just weeks after the landings, severe Channel storms battered the landing beaches wrecking one of the “Mulberries” (artificial breakwaters) and stopping the unloading of supplies for several days.

Operation Cobra, the intense aerial bombing assault on German forces on July 25th, by over 2,000 B-24’s and B-17’s from the 8th and 9th U.S. Air Forces, hammered the German units below. A German general said the bombers came like a conveyor belt resulting in 70% of the German forces in northwest Normandy either dead, wounded or shell shocked. Unfortunately, many areas in the planned bombing corridor were obscured by low lying cloud cover resulting in the deaths of many American soldiers. Casualties included 111 killed and 490 wounded GI’s by bombs dropped on supposedly “safe” areas. Despite these discouraging results, American infantry and armored units were now able to escape the labyrinth of Normandy hedgerows and country roads and raced south and east into the open fields and small towns of central France like a floodgate had been opened. The American Army pursued the retreating Germans in one of the fastest advances in the history of land warfare.

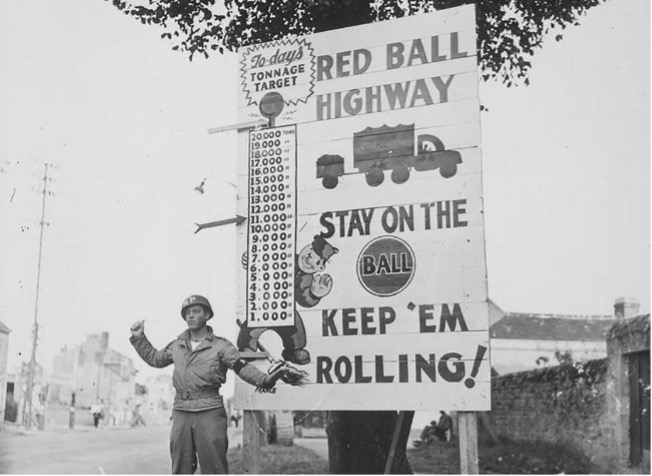

To expedite cargo shipment to the rapidly moving front, trucks emblazoned with red balls followed a similarly marked route that was closed to civilian traffic. The trucks also had priority on regular roads. The term “Red Ball” was used to describe express cargo service dated to the end of the 19th century. Around 1892, the Santa Fe Railroad began using it to refer to express shipping for priority freight and perishables. Trains and the tracks cleared for their use were marked with red balls. The term grew in popularity and was extensively used by the 1920s. Patton called the M135, 2½-ton, 6 wheel drive trucks, referred to as the “Deuce and a Half” as “our most valuable weapon.” Col. John Eisenhower, Ike’s son, said that without the Red Ball truck drivers “the advance across France would not have been made.” General Omar Bradley said without supplies “we could not move, shoot, or eat.”

At the beginning of World War II, Germany gained a reputation for its blitzkrieg (lightening war) mechanized attacks on Poland and Russia. In reality, the typical German division had ten times as many horse-drawn wagons as motorized vehicles to move men and material. Following the Cobra breakout, the German forces were astounded at the rapid American pursuit of their army. For example, following the breakout, elements of the U.S. Third Army, under General George S. Patton, Jr. often covered more than 75 miles a day. While the campaign forced the German Army to retreat across France, it also caused serious supply problems for the Allies. Patton’s gas-guzzling Sherman tanks averaged only 1.4 miles per gallon with a maximum range of 120 miles.

An armored division required 60,000 gallons a day. If the division had to go across country the figure soared. On top of the fuel, an armored division required thirty-five tons of rations per day for 21,000 men, including all those attached to it, and depending on the intensity of the fighting, a far greater tonnage of ammunition.

The Americans met the challenge with ruthless prioritization. “Supply trains” with fuel and oil received absolute priority. Each M-25 transporter (tanker) carried 16,000 gallons. They even used ammunition trucks “borrowed” from the artillery to haul more gasoline. Military police and Piper Cubs were employed to monitor the progress of every convoy, and engineers worked round the clock to improve roads and bridges.”

By the second week of August the demand for POL (petroleum, oil, and lubricants) had jumped from 300,000 gallons to 600,000 per day. Most of this was delivered by five ton trucks each hauling 125 five gallon “Jerry” (German style) cans of highly flammable fuel, each weighing about forty pounds.

Antony Beevor offered a perspective on the challenge in his history, D-DAY: the Battle for Normandy:

“According to General John C.H. Lee, the chief of SHAEF’s rear services, Patton tried to “appropriate the whole of fuel resupply for his own army.” He flattered the truck drivers, handing them Third U.S. Army parches, and sometimes he even commandeered the trucks to shift his infantry rapidly. This provoked exasperation and admiration in his colleagues.

According to Carlo D’Este’s Decision in Normandy:

“Patton used every subterfuge in his bag of tricks to keep the Third Army moving, including diversion of gasoline and ammunition destined for the First Army: on more than one occasion the Third Army troops obtained vital supplies by purporting to be from the First Army; trucks of the Red Ball Express were mysteriously diverted to Third Army supply dumps…Montgomery was incensed when he learned of these actions and complained loudly to Eisenhower; but the charade soon ended when the Third Army literally ran out of fuel outside Metz, where they remained for much of the autumn of 1944,”

The “Red Ball” convoy system began operating on August 25, 1944 and was staffed three-quarters with Black soldiers. Reflecting the racism of the time, the Army assigned Black troops almost exclusively to service and supply roles because it was believed they lacked the intelligence, courage, and skill needed to fight in combat units. Black soldiers were generally relegated to noncombat units regardless of their own desire to serve at the Front. (Military units were generally segregated by race until desegregation was ordered by President Truman in 1948.)

Most of the men were under the age of 24, typically 18 or 19, and few had experience driving trucks before the war. Driving a “deuce and a half” was not like driving an automobile. The 5,000-pound capacity trucks were primarily manufactured by General Motors (nicknamed “Jimmies’”), Dodge, and Ford, with some by Kaiser and Studebaker. The Dodge trucks were considered more reliable but replacement parts for the Jimmies were easier to come by. The standard trucks had a cargo bed 8 feet wide by 12 feet long, most with canvas tops.

Mileage was about 11 miles per gallon with a five speed, high and low range transmission with ten gears to master. The trucks were referred to as “six by sixes” with two front wheels and two pair in the rear. When needed, such as grinding through heavy mud or snow, all six wheels could be engaged. The four rear duals were powered by two drive shafts in the Jimmies which gave the trucks greater traction for hills, mud or snow. On the right of the floor mounted gear shift were two smaller levers. The right one engaged the front wheel drive, the left one gave the truck an extra low range in all gears. Drivers had to know how to use them all. Drivers had to know how to “double-clutch” and how and when to shift into all gears on the go. Drivers grew adept at driving in all road conditions including narrow, winding French village streets.