On 19 February 1945 — 79 years ago today — the US Marine Corps began the bloody work of taking Iwo Jima from the Imperial Japanese Army. Casualties were extremely heavy — nearly 7,000 Americans killed and close to triple that number wounded. In today’s article, Capt. Dale A. Dye, U.S.M.C. (ret.) describes his experiences in visiting that historic volcanic island.

Category: World War II – Pacific Theater

USS Montana arrives at new Pacific Fleet homeport in Hawaii

The Virginia-class fast-attack submarine USS Montana (SSN 794) arrived at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam following a change of homeport from Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia, December 23, 2024.

INDEPENDENT RECORD

By Lt. j.g. Paul Fletcher, Commander, Submarine Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet Public Affairs

The USS Montana, a Virginia-class fast-attack submarine, arrived Dec. 23 at its new Pacific Fleet homeport, Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam in Hawaii.

The $2.6 billion USS Montana, also known as SSN 794, changed its homeport from Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia, the U.S. Navy said in a news release. It marks the ninth Virginia-class fast-attack submarine home-ported at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam. It will be assigned to Submarine Squadron 1 and is expected to serve the nation with a range of missions around the world for more than three decades, officials said.

“We’re all very excited to be here in Pearl Harbor and we appreciate the great welcome,” Cmdr. John Gilligan, commanding officer of USS Montana, said in the news release.

He credited the crew for “extraordinary work in Virginia to get to this significant milestone.”

Capt. Aaron Peterson, commander, Submarine Squadron 1, met the Montana pier-side upon arrival.

“On behalf of the Pacific Submarine Force Ohana, I enthusiastically welcome the officers and crew of the good ship Montana, with the warmth, culture, and spirit unique to the state of Hawaii,” he said.

Before finishing its homeport shift from the East Coast, Montana completed a post-shakedown availability at Newport News Shipbuilding and was redelivered to the Navy in November 2024.

“Through a great effort by the crew, working with our industry partners, we’ve completed our availability and rejoined the Fleet. We’re ready to execute any task we’re called upon to complete throughout the Indo-Pacific,” Gilligan said.

Commissioned on June 25, 2022, at Naval Station Norfolk, Montana is the second warship to be named after the state, following the armored cruiser USS Montana (ACR 13).

The submarine is more than 377 feet long and can displace nearly 7,800 tons. Montana has a crew of nearly 140 sailors — all of whom have been named by Gov. Greg Gianforte as “honorary Montanans,” — and can support various missions, including anti-submarine warfare, anti-surface ship warfare, strike warfare, and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.

The U.S. Pacific Fleet Submarine Force provides strategic deterrence, anti-submarine warfare, anti-surface warfare, precision land strike, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and early warning and special warfare capabilities around the globe.

Ron Davis, chair of the Montana-based USS Montana Committee, praised the reaching of the milestone.

“It signals that the submarine is that much closer to being tasked to accomplish any of a number of different missions as part of the Pacific Fleet,” he said, adding the committee and all Montanans will continue to proudly support the Montana as it settles in Hawaii “and through her service life.”

The nonprofit, nonpartisan committee is a group of volunteers from across the state who support the USS Montana. It was endorsed by the governor and Legislature in 2017.

The ship is decorated with a Montana theme with state rooms named after Montana cities. Passageways are named for Montana rivers. The crew mess area, called the Big Sky Saloon, includes a Glacier Park panorama.

The submarine also has a tribal victory/war song to be played aboard the submarine when the crew is called to battle stations. And in honor of the Treasure State’s past of vigilante justice in the 19th century, the crew has adopted the nickname “The Vigilantes of the Deep.”

For more information, go to: https://ussmontanacommittee.us/.

‘Bomb-blasted American foothold”: How a Butte man survived Wake Island, life as POW in WWII

By Tracy Thornton, Montana Standard

Shortly before 8 a.m. on a Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese began their assault on the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor. The two-hour surprise attack killed an estimated 2,403 American men and women, and nearly decimated the U.S. Naval fleet.

Five hours later, the Japanese would begin another bombing raid 2,300 miles away, at Wake Island and its smaller islands, Peale and Wilkes. Stationed on the islands were nearly 525 U.S. military personnel — the majority being Marines and sailors. More than double that amount was the number of American civilian workers also on the island, there to construct military facilities.

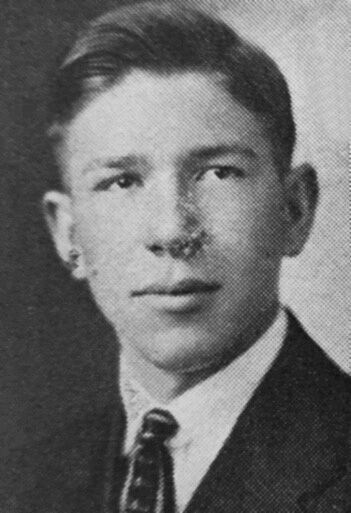

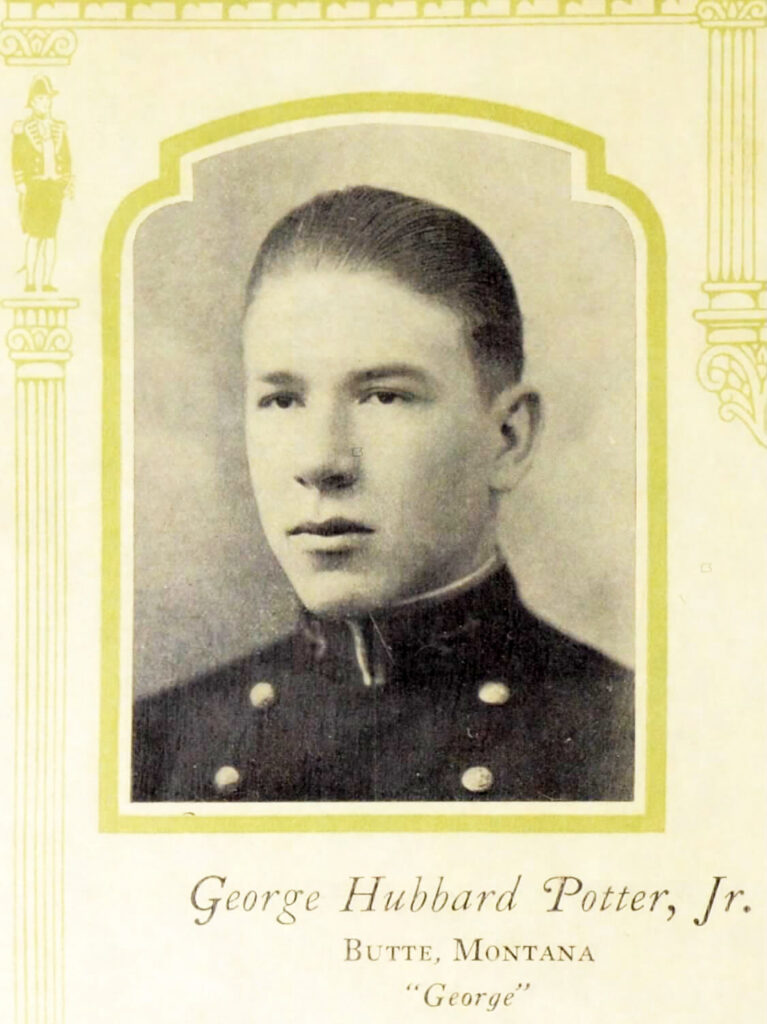

The troops on Wake Island fought the good fight; combatants included a Butte man, Major George Hubbard Potter Jr., who was second in command. In the end, though, the Americans were far outnumbered and surrendered two days before Christmas.

Major Potter, with the Marine Corps’ 1st Defense Battalion, previously was stationed at Pearl Harbor, where his wife Octavia and infant son George lived, but was shipped to Wake Island in October 1941.

Potter would spend the rest of the war as a prisoner of war. “Allied troops who had the misfortune to be taken prisoner by the Japanese during World War II quickly learned that the Geneva Convention might as well not exist. Indeed, they endured years of not only malnutrition and starvation, disease and general neglect — resisting all the while — but also torture, slave labor and other war crimes,” according to a 2016 article published by the U.S. Army.

The son of George and Helen Potter, the younger Potter was born in 1906 in Ennis. His family, including two brothers, Ralph and Clyde, moved to Butte when he was young. A student at Webster Grade School, Potter graduated from Butte High School in 1923. Nicknamed “Gorg,” as a senior, he was president of the school’s mathematics club.

Potter would continue his education at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, graduating in 1927, and was then commissioned a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps.

Being a Marine was Potter’s chosen career. By 1936, he was a captain and later promoted to major.

After the Wake attack Potter was a POW for the next three years and eight months. He remained on Wake Island for Christmas 1941, but by Jan. 15, 1942, was a passenger aboard the Nitta Maru, a Japanese aircraft carrier, bound for Zentsuji, a prison camp in Japan. En route to the prison camp, five American sailors aboard that same ship were beheaded and then thrown overboard.

The only prisoners left on Wake Island were 98 American civilian workers, forced to work on various projects. According to the U.S. Naval Institute, all the men were executed by Japanese soldiers and buried in a mass grave on Oct. 7, 1943, “to eliminate the threat they might pose during the coming invasion” with American forces.

It wasn’t until April 1942 that Potter’s wife would receive any word from her husband. A message from Potter to his wife was broadcast via radio.

He said, in part, “Do not be worried about me. I’ll be all right but I am most concerned for your and the baby’s welfare, and about dad’s health.”

Potter would remain at Zentsuji until June 23, 1945, when he would be transferred to a camp located in the hills of Honshu, Japan.

Now 50 pounds lighter, he would be liberated from this camp not long after Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, 1945.

In a post-war interview, Potter, who by then had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel, shared his war experiences with a Montana Standard reporter.

“The dwindled Yank force dug deeper and fought more fiercely for the bomb-blasted American foothold,” he said of the initial Battle of Wake Island.

Potter also talked about life in the POW camps, specifically Zentsuji.

“The Americans at the camp included 350 officers, enlisted men, nurses, and a few civilians,” he said.

Potter also stressed that the treatment of prisoners escalated as the war progressed. When it became clear that Allied forces would soon win the war, the atrocities got even worse.

“They became progressively that way as the tide of war set against them,” said Potter.

After serving 21 years, Potter, who would become a brigadier general, would retire from the Marine Corps in August 1948. The former Butte man died Sept. 17, 1983, in Florida, and is buried, along with his wife Octavia, at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Liberator: A Gift From Above Podcast

Montana’s Participation in World War II

Information highlighting some but not all, of Montana’s participation in the Second World War, or as it is known, World War II. It is provided it to you as a testament to Montana’s World War II generation, their dedication to duty and sacrifice to keep our nation free from tyranny.’ While May 8th was being celebrated as V-E day in Europe, many Montanans were fighting in the Battle of Okinawa. The Battle of Okinawa (April 1, 1945-June 22, 1945) was the last major battle of World War II, and one of the bloodiest. On April 1, 1945—Easter Sunday—the Navy’s Fifth Fleet and more than 180,000 U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps troops descended on the Pacific island of Okinawa for a final push towards Japan. The invasion was part of Operation Iceberg, a complex plan to invade and occupy the Ryukyu Islands, including Okinawa. Though it resulted in an Allied victory, kamikaze fighters, rainy weather and fierce fighting on land, sea and air, it led to a large death toll on both sides. Montana’s 163rd Infantry Regiment Montana’s 163rd Infantry Regiment, 41st Infantry Division, the Jungleers, was called to Active duty on September 16, 1940 for one year of training, and on the same day the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 introduced the first peacetime conscription (for men between 21 and 45) in United States history. • March 11, 1941: United States President Roosevelt established the Lend Lease Act allowing Britain, China, and other allied nations to purchase military equipment and to defer payment until after the war. • August 1941: President Roosevelt signed an extension of service of 6 months for those Americans who been called up in 1940, such as the 163rd Infantry training at Fort Lewis, Washington. • December 7, 1941: The United States came under attack by Japanese Forces at Pearl Harbor and locations throughout the Pacific. • December 8, 1940: The United States declared War on Japan. • December 11, 1940: Germany and Italy declare war on the United States. The United States reciprocates and declares war on Germany and Italy. The largest ever mobilization of American manpower continued, ultimately calling up over 15 million U.S. men and women to serve from 1941 to the end of hostilities in 1945. Over 75,000 Montanans were a part of that force. The 163rd Infantry Regiment served with distinction on the west coast of the United States until its departure to Australia in April 1942. This Regiment served as a part of the Southwest Pacific Command going on to fight in the Pacific Theater of World War II. The 163rd Infantry Regiment was recognized as the first U.S. unit to defeat Imperial Japanese Forces in the Battle of Sanananda, Papua, New Guinea in January 1943. It was subsequently recognized by the 28th Montana Legislative Assembly by resolution and in a famous painting by Irwin ‘Shorty’ Shope in April 1943. The 163rd Infantry Regiment served in the Pacific Theater in three major campaigns and a battle; the Papuan Campaign of 1943, winning the battles at Sananada, Gona, and Kumsi River; the New Guinea Campaign of 1944, winning the battles of Aitape, Wadke and ‘Bloody” Biak; the Southern Philippines Campaign of 1945, winning battles at Zamoanga, Sanga Sanga Island; and the Battle of Jolo and the key village of Calinan against seasoned Japanese land forces. This battle was stopped only because of the cessation of hostilities due to the dropping of the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Regiment finally became an occupation force on the Japanese mainland. The 163rd was demobilized in Japan, January 1, 1946, and sent home by ships. First Special Service Force The First Special Service Force was a joint US-Canadian special operations force secretly formed at Fort William Henry Harrison near Helena, Montana in July 1942, to organize and train for Operation Plough. Operation Plough included plans to attach a hydro-electric target in German-held northern Norway responsible for creating heavy water for Germany’s atomic bomb. The unit went on to serve in both the Pacific theater and European theaters, with battle credits in the Aleutians, Naples –Foggia, Rome –Arno, Southern France, the Rhineland and Southern France. They were inactivated December 1944 without losing a battle and with battle casualties’ equivalent to 137 % of its strength. Camp Rimini War Dog Reception and Training Center Camp Rimini War Dog Reception and Training Center was established at Camp Rimini, west of Helena where it trained as a part of the effort to disrupt the Axis power. It went on to acquit itself along military air routes as search and rescue services. They provided specialized transport in remote areas of the Northern Hemisphere such as Newfoundland and in Europe during winter operations as providing transport of war materiel to our American forces. 7th Ferrying Command, Air Transport Command The Army Air Force organized and trained bomber forces throughout Montana at such locations as Great Falls, Lewistown, and Cutbank. The 7th Ferrying Command, Air Transport Command was formed at Great Falls (Gore Hill) and at East Base (now Malmstrom AFB), Montana to carry out the mission of providing aircraft and critical supplies to our allies over the Great Circle Route, a critical part of Global War Air Operations. Fort Missoula Fort Missoula became an alien detention camp housing Italian sailors who had been caught up in the war from 1942 to 1943. After working with local farmers and ranchers, many of the men went on to immigrate to the United States. Triple Nickels Specialized units such as the African-American, segregated, 555th Parachute Battalion, known as the Triple Nickels, trained and fought forest fires throughout Montana and the Northwest. The Home Front The people of Montana supported the war effort in many ways on the Home Front, providing food, and other strategic supplies and minerals, meeting or exceeding the quotas for the eight War Bond Drives. Montanans support, fought, were wounded and died in all theaters of World War II. As Joseph Howard Kinsey wrote in his book “High, Wide, and Handsome” of the more than 15 million men and women in the U.S. armed forces during “World War II, Montana furnished 75,000” to the effort. “Proportionately this was near the top of all states. In World War II, as in World War I, Montanans were quick to enlist and they were healthy; the proportion rejected because of physical defect was smaller than the national average. Montana’s death rate in World War II was only exceeded by that of New Mexico in proportion to population.”

Victory over Japan Day (V-J Day)

“I deem this reply a full acceptance of—the unconventional surrender of Japan--.” President Truman

Victory over Japan Day (also known as V-J Day) was announced by President Harry S. Truman in the following statement: “I have received this afternoon a message from the Japanese government in reply to the message forwarded to that government by the secretary of state on Aug. 11, 1945. I deem this reply a full acceptance of the Potsdam declaration which specifies the unconditional surrender of Japan—.” A little after noon Japan Standard Time on August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito’s announcement of Japan’s acceptance of the terms of Potsdam Declaration was broadcast to the Japanese people over the radio. Earlier the same day, the Japanese government had broadcast over Radio Tokyo that the “acceptance of the Potsdam Proclamation [would be] coming soon”, and had advised the Allies of the surrender by sending a cable to U.S. President Harry S. Truman via the Swiss diplomatic mission in Washington D.C. A nationwide broadcast by Truman was aired at seven o’clock p.m. (daylight savings time, Washington, D.C.) on Tuesday, August 14 announcing the communication and that a formal event was scheduled for September 2. In his announcement of Japan’s surrender on August 14 Truman said that “the proclamation of V-J Day must wait for the formal signing of surrender terms by Japan.” After news of the Japanese acceptance and before Truman’s announcement, Americans began celebrating “as if joy had been rationed and saved up for three years, eight months, and seven days since Sunday, December 7, 1941.”

Montana’s 163rd Infantry Regiment, 41st Infantry Division

Montana’s 163rd Infantry Regiment, 41st Infantry Division, the Jungleers, was called to active duty on September 16, 1940 for one year of training, and on the same day the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 introduced the first peacetime conscription (for men between 21 and 45) in U.S. history. March 11, 1941: United States President Roosevelt established the Lend Lease Act allowing Britain, China and other allied nations to purchase military equipment and to defer payment until after the war. Roosevelt signed an extension of service of six months for those Americans who had been called up in 1940, such as the 163rd Infantry training at Fort Lewis, Washington. December 7, 1941: The U.S. came under attack by Japanese forces at Pearl Harbor and locations throughout the Pacific. December 8, 1940: The U.S. declared war on Japan. December 11, Germany and Italy declare war on the U.S. The U.S. reciprocates and declares war on Germany and Italy. The largest ever mobilization of American manpower continued, ultimately calling up over 15 million U.S. men and women to serve from 1941 to the end of hostilities in 1945. Over 75,000 Montanans were a part of that force. The 163rd Infantry Regiment served with distinction on the west coast of the U.S. until its departure to Australia in April 1942 as a part of the Southwest Pacific Command going on to fight in the Pacific Theater of World War II. The 163rd Infantry Regiment was recognized as the first U.S. unit to defeat Imperial Japanese Forces in the Battle of Sanananda, Papua, New Guinea in January 1943; subsequently being recognized by the 28th Montana Legislative Assembly by resolution and the famous painting by Irwin ‘Shorty’ Shope in April 1943. The 163rd Infantry Regiment served in the Pacific Theater in three major campaigns: • The Papuan Campaign 1943, winning the battles at Sananada, Gona, and Kumsi River • The New Guinea Campaign 1944, winning the battles of Aitape, Wadke and ‘Bloody” Bia • The Southern Philippines Campaign 1945, wining battles at Zamoanga, Sanga Sanga Island, and the Battle of Jolo and the key village of Calinan The 163rd fought against seasoned Japanese land forces, stopping only because of the cessation of hostilities due to the dropping of the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and finally becoming an occupation force on the Japanese mainland. The 163rd was demobilized in Japan, January 1, 1946, and sent home by ships.