By Tracy Thornton, Montana Standard

Shortly before 8 a.m. on a Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese began their assault on the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor. The two-hour surprise attack killed an estimated 2,403 American men and women, and nearly decimated the U.S. Naval fleet.

Five hours later, the Japanese would begin another bombing raid 2,300 miles away, at Wake Island and its smaller islands, Peale and Wilkes. Stationed on the islands were nearly 525 U.S. military personnel — the majority being Marines and sailors. More than double that amount was the number of American civilian workers also on the island, there to construct military facilities.

The troops on Wake Island fought the good fight; combatants included a Butte man, Major George Hubbard Potter Jr., who was second in command. In the end, though, the Americans were far outnumbered and surrendered two days before Christmas.

Major Potter, with the Marine Corps’ 1st Defense Battalion, previously was stationed at Pearl Harbor, where his wife Octavia and infant son George lived, but was shipped to Wake Island in October 1941.

Potter would spend the rest of the war as a prisoner of war. “Allied troops who had the misfortune to be taken prisoner by the Japanese during World War II quickly learned that the Geneva Convention might as well not exist. Indeed, they endured years of not only malnutrition and starvation, disease and general neglect — resisting all the while — but also torture, slave labor and other war crimes,” according to a 2016 article published by the U.S. Army.

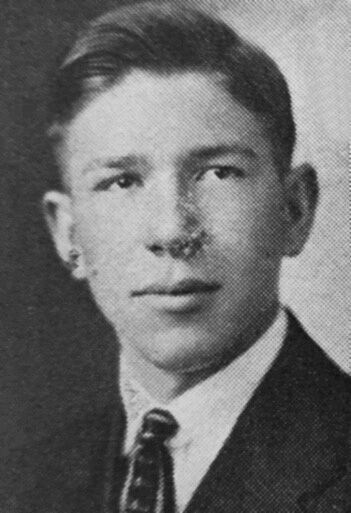

The son of George and Helen Potter, the younger Potter was born in 1906 in Ennis. His family, including two brothers, Ralph and Clyde, moved to Butte when he was young. A student at Webster Grade School, Potter graduated from Butte High School in 1923. Nicknamed “Gorg,” as a senior, he was president of the school’s mathematics club.

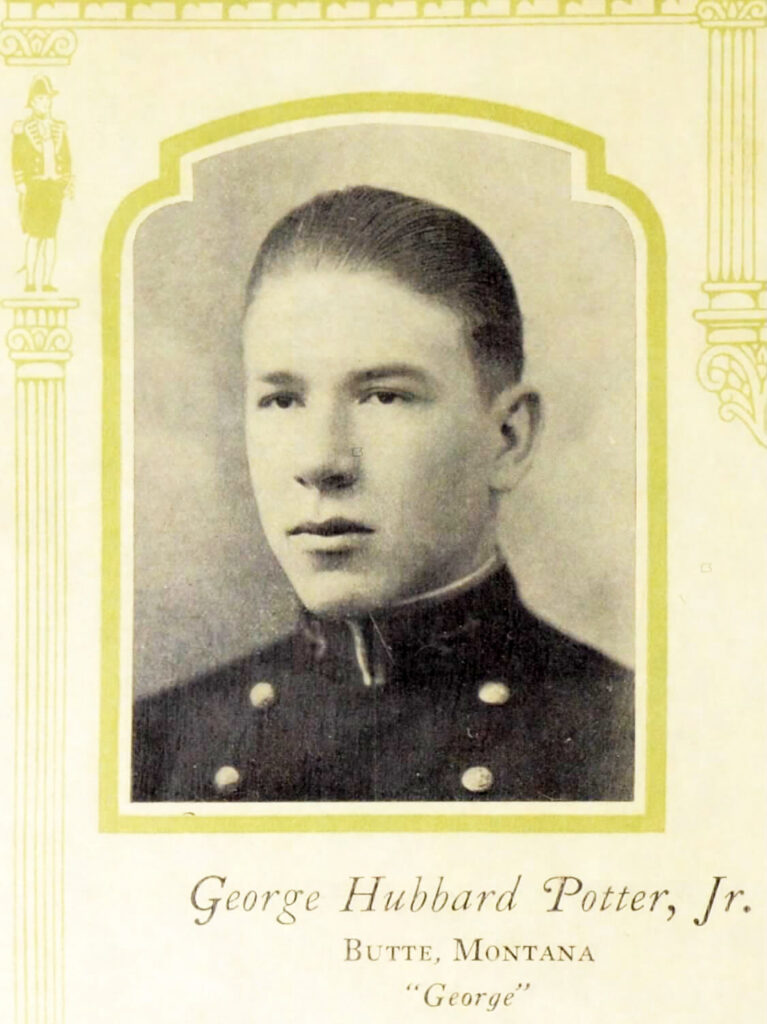

Potter would continue his education at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, graduating in 1927, and was then commissioned a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps.

Being a Marine was Potter’s chosen career. By 1936, he was a captain and later promoted to major.

After the Wake attack Potter was a POW for the next three years and eight months. He remained on Wake Island for Christmas 1941, but by Jan. 15, 1942, was a passenger aboard the Nitta Maru, a Japanese aircraft carrier, bound for Zentsuji, a prison camp in Japan. En route to the prison camp, five American sailors aboard that same ship were beheaded and then thrown overboard.

The only prisoners left on Wake Island were 98 American civilian workers, forced to work on various projects. According to the U.S. Naval Institute, all the men were executed by Japanese soldiers and buried in a mass grave on Oct. 7, 1943, “to eliminate the threat they might pose during the coming invasion” with American forces.

It wasn’t until April 1942 that Potter’s wife would receive any word from her husband. A message from Potter to his wife was broadcast via radio.

He said, in part, “Do not be worried about me. I’ll be all right but I am most concerned for your and the baby’s welfare, and about dad’s health.”

Potter would remain at Zentsuji until June 23, 1945, when he would be transferred to a camp located in the hills of Honshu, Japan.

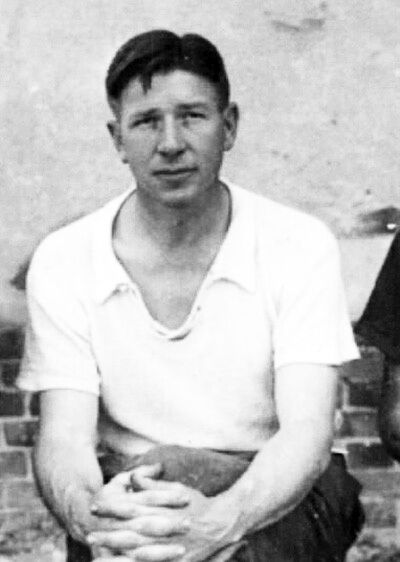

Now 50 pounds lighter, he would be liberated from this camp not long after Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, 1945.

In a post-war interview, Potter, who by then had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel, shared his war experiences with a Montana Standard reporter.

“The dwindled Yank force dug deeper and fought more fiercely for the bomb-blasted American foothold,” he said of the initial Battle of Wake Island.

Potter also talked about life in the POW camps, specifically Zentsuji.

“The Americans at the camp included 350 officers, enlisted men, nurses, and a few civilians,” he said.

Potter also stressed that the treatment of prisoners escalated as the war progressed. When it became clear that Allied forces would soon win the war, the atrocities got even worse.

“They became progressively that way as the tide of war set against them,” said Potter.

After serving 21 years, Potter, who would become a brigadier general, would retire from the Marine Corps in August 1948. The former Butte man died Sept. 17, 1983, in Florida, and is buried, along with his wife Octavia, at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.