The 41 st Infantry Division in the South Pacific

DIVISION CHRONICLEThe 41st Infantry Division arrived in Australia, 7 April 1942, and underwent intensive training. The 163d Regiment entered the struggle for the defense of Port Moresby, New Guinea, at Dobadura, 2 January 1943, and fought continuously along the Sanananda track until the 22d. A period of patrolling and training followed while elements of the Regiment advanced against stiff resistance to the Kumisi River in February. The 163d left for Australia, 15 July 1943. The 162d Regiment relieved the 163d in the Sanananda- Killerton-Gona area and the outpost area at the mouth of the Kumisi River, February 1943, leapfrogged along the coast in the Morobe area, and fought the long Salamaua campaign, 29 June 1943 to 12 September 1943. On 22 April 1944, the 163d Regiment landed at Aitape while the remainder of the Division came ashore at Humboldt Bay near Hollandia. Hollandia and the Cyclops and Sentani Airdromes fell after ineffectual resistance, and the Division patrolled and moppedup until relieved on 4 May. The 163d landed against slight opposition at Arara, 17 May, and consolidated the Arara and Toem area. Wakde Island was taken, 1820 May. Biak Island was invaded, 27 May, and a period of harsh jungle fighting followed. Elements landed at Korim Bay and Wardo, 17 August, to prevent an enemy escape, and the Division was occupied with patrols and training until 8 February 1945. On that date, it arrived at Mindoro, Philippine Islands. On 28 February, the 186th landed on Palawan Island, completing the occupation by 8 March. The rest of the 41st landed at Zamboanga, Mindanao, 10 March, against light initial resistance. The enemy fought fiercely until opposition was dissipated early in April. Elements took Basilan Island unopposed, 16 to 30 March, Sanga-Sanga, 2 April, and Jolo, 9 April. While elements fought northwest of Davao, the rest of the Division continued patrolling and mopping up activities in the Southern Philippines until VJday. Occupational duty followed in Japan until inactivation. Source: Downloaded from usarpac.army.mil March 25, 2024

The Papua Campaign

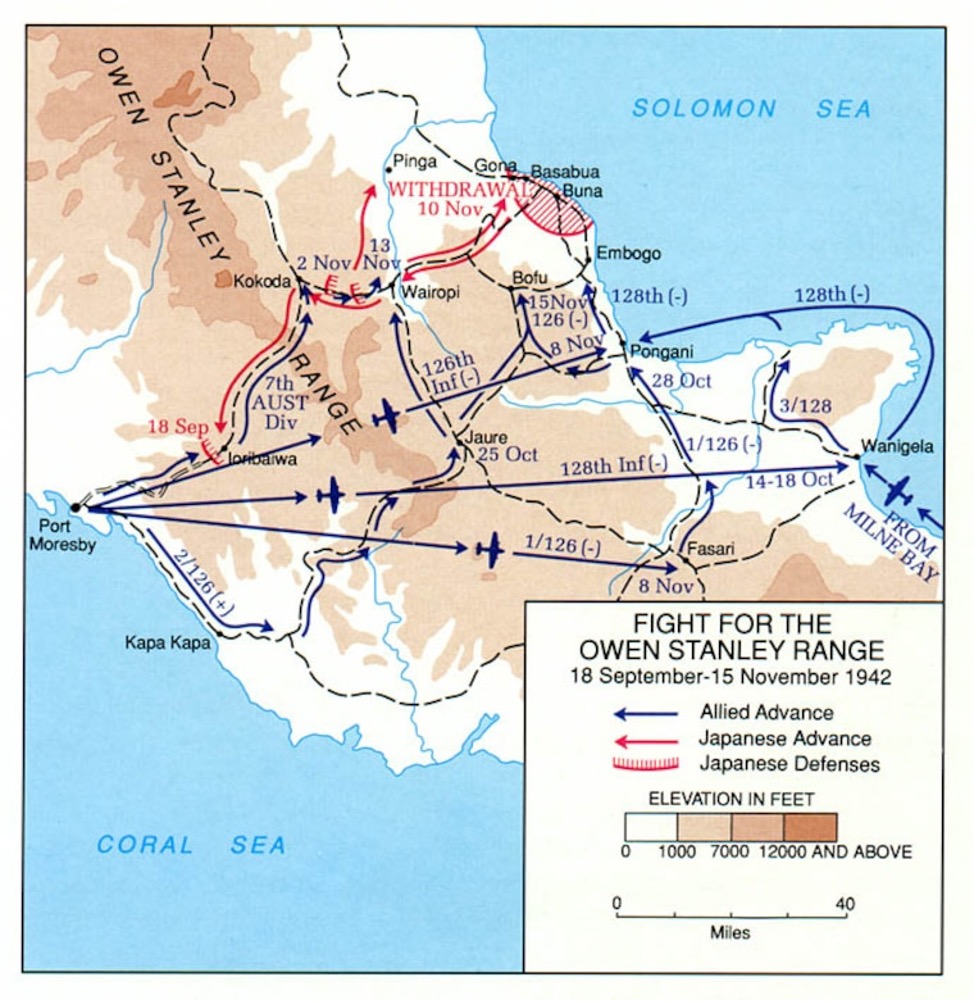

By Dr. Mike Krivdo / Published Feb. 8, 2023 80 years ago, on 22 January 1943, American and Australian forces ended their first major campaign of WWII in the Pacific. It was also their first success after suffering a string of losses throughout the Pacific, as the Japanese quickly occupied Allied strongholds such as Hong Kong, Singapore, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies. In the Southwest Pacific Area, the Japanese Army’s strategic goal was the capture of the Papuan capital city of Port Moresby. By taking it, the Japanese hoped to sever the sea lines of communication between the U.S. and Australia, cutting the vital supply lines. Japan’s first attempt was by sea, launching a strong Naval Task Force into the Coral Sea. However, the Japanese were dealt a setback. The Japanese lost naval superiority in the Battles of Coral Sea (4-8 May 1942) and Midway (4-7 June 1942), forcing them to attempt to seize Port Moresby by land. Occupying Buna in the north of Papua, the Japanese Army attacked south through the mountainous, heavily jungled trails over the Owen Stanley Mountains, over 13,000 ft. in elevation. The Allies moved quickly to interdict, pushing troops piecemeal into battle as they arrived in theater. Both sides fought hard for control of the Kokoda Trail, a jungle path that crossed the Stanleys and entered Port Moresby from the north. In addition to the horrendous terrain, Soldiers on both sides had to contend with other challenges that made combat in Papua a living hell. The thick vegetation limited observation to a few yards, making it difficult to effectively engage the enemy at a distance with supporting arms. The weather also complicated operations. At low levels the high temperatures, humidity and rainfall wore down combatants; at higher altitudes the temperatures dropped. Rainfall averaged ten inches a day, turning trails to muddy bogs and swelling streams to rivers. Soldiers could not stay dry and their clothes rotted off their bodies. Sharp Kunai grass 7 feet high cut skin, opening wounds that wouldn’t heal. Mosquitos, leeches, and disease attacked voraciously. The Army also had to develop new ways of sustaining the force. Trafficability was bad, forcing troops to manpack food, water, and ammo, wearing them down. The high heat turned rations rancid, leading to development of better jungle rations. Creative use of boats, airdrops, animals, and porters were developed to keep supplies moving forward. The experience gained in this campaign carried over to later campaigns, allowing Army logistics to perform at a high rate of success. They also learned the value of airfields. The first American troops (32 nd and 41 st Infantry Divisions) arrived incrementally and reinforced Australian defenders, worn out from months of combat. They were organized into a new I Corps command under MG Robert L. Eichelberger. Soon, the combined effort began achieving success against the enemy. By early August, the Allies had secured Kokoda and were using its airfield to push the Japanese back toward Buna. In early September, a Japanese flanking attack at Milne Bay was repulsed, strengthening the Allies’ situation. A multiple-axis attack in October pushed the Japanese back into Buna, leading to a drive in November by the newly-arrived 127 th Infantry Regiment. In late December the Japanese had been pushed out of Buna into Sanananda, where they would fight on until surrendering on 22 January, bringing the Papua Campaign to an end. The Army’s entry into the fight had been costly, but they learned a lot. The Papua veterans suffered greatly; in the 32nd ID alone, 66 percent suffered from some sickness. More than 650 had been killed in combat and another 2,500 wounded. Artillery planners learned new ways of providing effective support. The value of airfields and air support was reinforced, as were new means of employing naval gunfire by attacking forces. Most of all, the Army relearned the value of proper preparation and training of troops before they were committed to battle. The lessons of Papua were disseminated to train every Soldier entering the Pacific Theater in the tactics, techniques, and procedures needed to be successful in combat against the Japanese. Source: Downloaded from usarpac.army.mil March 25, 2024163 Infantry Regiment > Yank Magazine 1943

163 Infantry Regiment at Buna > Jungleer 1958 May p5&7

163 Infantry Regiment 1st Battalion > Jungleer 1975 Mar p5-6

163 Infantry Regiment A Company > Jungleer 1981 Jul p13-14

163 Infantry Regiment A Company > Jungleer 1995 Feb p14-16

163 Infantry Regiment A Company (Also AT Co.) > Jungleer 1970 Sep p5&6

163 Infantry Regiment Also 116 Medical Battalion > Jungleer 1994 Nov p23-25

163 Infantry Regiment B Company > Jungleer 1985 Nov p7-9

163 Infantry Regiment B Company > Jungleer 1987 Aug p17-18

163 Infantry Regiment B Company > Jungleer 1975 Sep p20-22

163 Infantry Regiment B Company (Also C Co.) > Jungleer 1973 Dec p10-11

163 Infantry Regiment B Company (Also C Co.) > Jungleer 1974 Jun p10-11

163 Infantry Regiment C Company > Jungleer 1986 Nov p20-22

163 Infantry Regiment C Company (Also A&B Cos.) > Jungleer 1978 Oct p20-23

163 Infantry Regiment Chaplain > Jungleer 1969 Sep p3-4

163 Infantry Regiment D Company > Bulletin Board 2005 Dec p6-12

163 Infantry Regiment E Company > Jungleer 1981 Jul p6, 16

163 Infantry Regiment E Company > Jungleer 1993 May p20-22

163 Infantry Regiment E Company (Also F & G Cos.) > Jungleer 1967 Aug p5-6

163 Infantry Regiment E, F,& G Companies > Jungleer 1958 Feb p4

163 Infantry Regiment F Company > Jungleer 1977 Jul p23-25

163 Infantry Regiment F Company > Jungleer 1989 Aug p18-20

163 Infantry Regiment F Company (Also G Co.) > Jungleer 1960 Jun p4-5

163 Infantry Regiment G Company > Jungleer 1983 Jul p15-16

163 Infantry Regiment G Company (Also 2nd Bn.) > Jungleer 1974 Sep p20-21

163 Infantry Regiment G Company (Also 2nd Bn.) > Jungleer 1976 Mar p8-10

163 Infantry Regiment H Company > Jungleer 1995 Nov p21-22

163 Infantry Regiment I Company > Jungleer 1969 Sep p7-8

163 Infantry Regiment K Company (3rd Battalion) > Jungleer 1976 Dec p15-16

163 Infantry Regiment L Company (Also K Co.) > Jungleer 1975 Jun p5-6

163 Infantry Regiment L Company > Jungleer 1991 Aug p18-20

163 Infantry Regiment M Company Jungleer 1958 Jul p4