Following the Québec Conference in August 1943, General Dwight D. Eisenhower was moved to London to plan for the Normandy landings. Command of the Mediterranean Theater was given to British General Henry Maitland Wilson. General Sir Harold Alexander, commanding the Allied Armies in Italy, had formulated the plan to land Allied troops at Anzio in order to outflank German positions in the area. German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring commanded the four German divisions at Anzio, which included the Hermann Goering Division and the 35th Panzer Grenadier Regiment of the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division Reichsführer-SS Division. Combined German and Italian strength at Anzio was an estimated 70,000 men.

The Special Force brigade was withdrawn from the mountains in January and on 1 February was landed at the beachhead created by Operation Shingle at Anzio, south of Rome, replacing the 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions, which had suffered heavy losses at the Battle of Cisterna. Their task was to hold and raid from the right-hand flank of the beachhead marked by the Mussolini Canal/Pontine Marshes. First Regiment was positioned on the Force’s right front, which comprised one-third of the entire line, while the 3rd Regiment guarded the remaining two-thirds of the line. Second Regiment, which had been reduced to three companies following the attacks on La Difensa, Sammucio and Majo, were tasked with running night patrols into Axis territory. Shortly after the FSSF took over the Mussolini Canal sector, German units pulled back up to 0.5 miles (0.80 km) to avoid their aggressive patrols. The Force’s constant night raids forced Kesselring to fortify the German positions in their area with more men than he had originally planned. Reconnaissance missions performed by the Devil’s often went as deep as 1,500 feet (460 m) behind enemy lines.

Frederick was greatly admired by the soldiers of the FSSF for his willingness to fight alongside the men in battle. On the beachhead in Anzio, for example, a nighttime Force patrol walked into a German minefield and was pinned down by machine gun fire. Colonel Frederick ran into battle and assisted the litter bearers in clearing the wounded Force members.

German prisoners were often surprised at how few men the Force actually contained. A captured German lieutenant admitted to being under the assumption that the Force was a division. Indeed, General Frederick ordered several trucks to move around the Forces area in order to give the enemy the impression that the Force comprised more men than it actually did. An order was found on another prisoner that stated that the Germans in Anzio would be “fighting an elite Canadian-American Force. They are treacherous, unmerciful and clever. You cannot afford to relax. The first soldier or group of soldiers capturing one of these men will be given a 10-day furlough.”

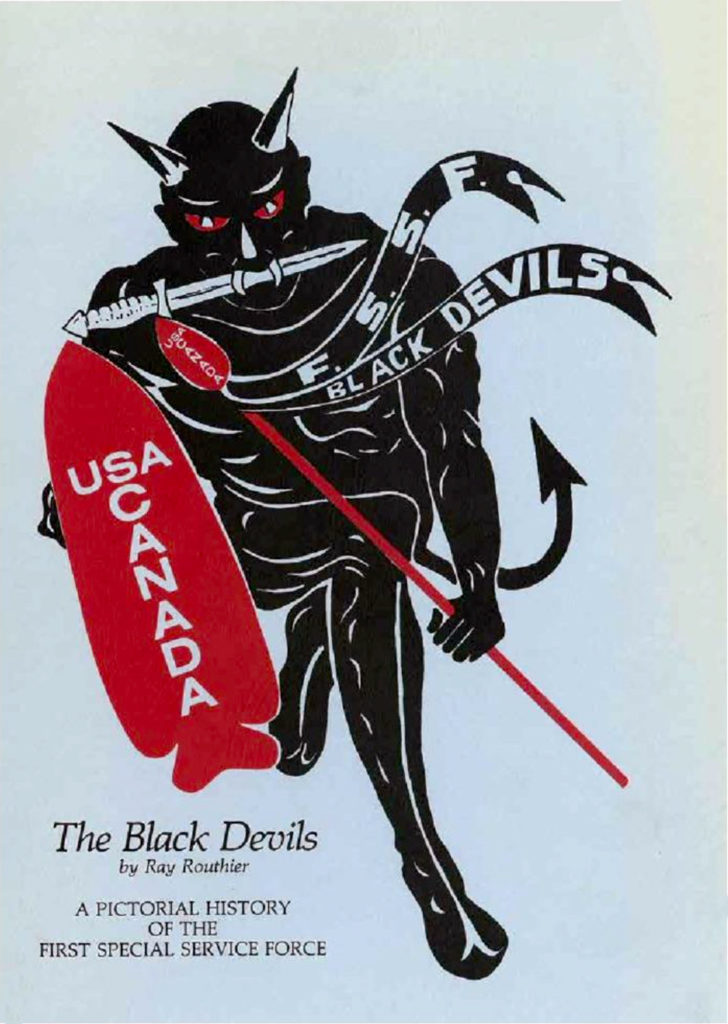

It was at Anzio that the Germans dubbed the FSSF the “Black Devils.” There is no record of any German ever referring to the Force as “The Devil’s Brigade.” They were referred to as “black” devils because the Brigade’s members smeared their faces with black boot polish for their covert operations in the dark of the night. During Anzio, the FSSF fought for 99 days without relief. It was also at Anzio that the FSSF used their trademark stickers; during night patrols soldiers would carry stickers depicting the unit patch and a slogan written in German: “Das dicke Ende kommt noch,” said to translate colloquially to “The worst is yet to come”. They placed these stickers on the bodies of German soldiers as well as fortifications. Canadian and American members of the Force who lost their lives are buried near the beach in the Commonwealth Anzio War Cemetery and the American Cemetery in Nettuno, just east of Anzio.

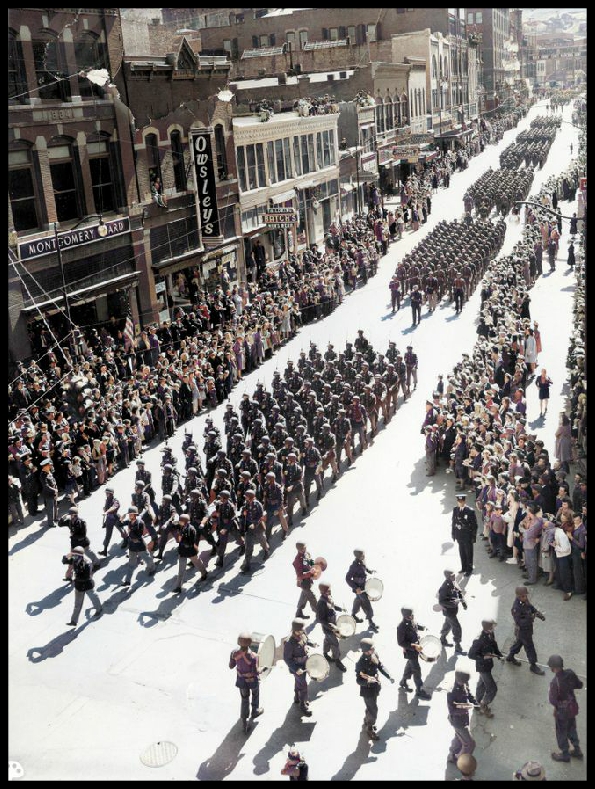

When the U.S. Fifth Army’s breakout offensive began on 25 May 1944, the FSSF was sent against Monte Arrestino, and attacked Rocca Massima on 27 May. The FSSF was given the assignment of capturing seven bridges in the city to prevent their demolition by the withdrawing Wehrmacht. During the night of 4 June, members of the FSSF entered Rome, the first Allied unit to do so. After they secured the bridges, they quickly moved north in pursuit of the retreating Germans.

In August 1944 FSSF came under the command of Colonel Edwin Walker when Brigadier General Frederick, who had commanded the Force since its earliest days, left on promotion to major general to command the 1st Airborne Task Force.