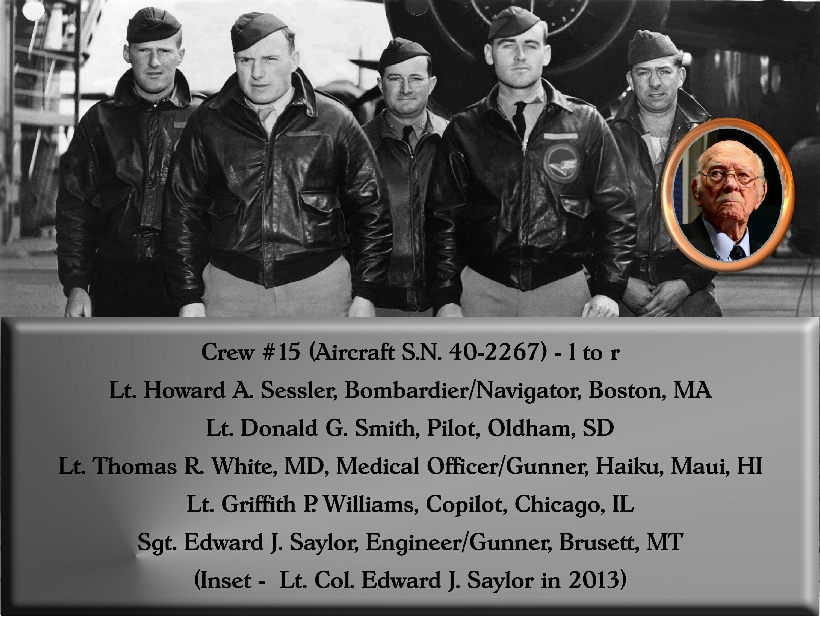

Lieutenant Colonel Saylor was born in 1920 and grew up on a ranch near Brusett, Montana, operated by his father, a Spanish-American War veteran. Times were tough and in 1939, at age 19, he enlisted in the army, saying he “needed a job”. Two brothers, John and Dan, also enlisted. Dan was later killed in Italy and earned a Silver Star for bravery in action. As a fan of airplanes and a natural mechanic, Ed joined the Army Air Corps as a maintenance technician. After the war he accepted a commission in the Air Force and retired as a Lieutenant Colonel after 28 years of distinguished service in aircraft maintenance. The Saylor Hangar at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida is named in his honor. In later life he took up a hobby of working with stained glass, and the replica of the B-25 flying through the sun’s rays (symbolic of the Japanese flag at the time) is a gift from him to the Montana Military Museum. He resided in Enumclaw, Washington, speaking often to local schools and fraternal organizations at the time of his death in 2015.